When Henry Luce, the owner of Time, bought Life magazine in 1936, he wanted to achieve many things. Among them, “to see man’s work — his paintings, towers and discoveries”.

What we don’t realize is his vision was partly captured by the female gaze and now, the photography of six women, who were on staff at Life, will be on view at the New York Historical Society. The exhibition, Life: Six Women Photographers, features over 70 images by the women who worked there between the 1930s and 1970s — a time when female photojournalists were a rarity.

“Many of these women are not known, they’re not even in photography history books,” said Marilyn Kushner, who co-curated the exhibit with Sarah Gordon, Erin Levitsky and William J Simmons. “These women have not gotten their due, and this is just the tip of the iceberg.”

Kushner wanted to draw attention to the work of these overlooked women by featuring some of their best work; from war photos to weddings, from capturing women’s housework to images of soldiers and labor unions. Their contribution to the magazine inevitably expanded, or changed, Luce’s initial vision of putting the lens on “men’s work”.

Kushner and her curatorial team started out by sifting through thousands of photos at the Life Picture Collection. “One thing that came to mind was what about the women photographers; who were they?” she asks. “It turns out, there were less than 10 women photogs on staff, so we wanted to highlight them as an integral part of what was going on at the magazine.”

The exhibit features the works of Bronx-born photographer Margaret Bourke-White, one of the founding photojournalists at Life, whose photo of the Fort Peck Dam in Montana graced the cover of the magazine’s first issue. She was also the first American female photographer to cover the second world war.

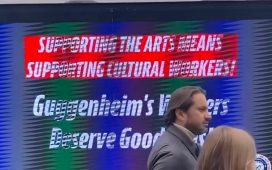

There are also the works of German photographer Hansel Mieth, who fled her hometown at the age of 15, to live in America. She covered working class America in the 1930s and 1940s, and in 1938, she did a series about the International Ladies’ Garment Workers, where she captured lively shots of female workers, many of who were smiling.

“These photos have a female outlook,” said Kushner, “and some of these stories are best told by women.”

Also on view are photos by Lisa Larsen, who covered the cold war. She was assigned to cover the Kremlin visit of Yugoslavia’s President Josip Broz in 1956. While working in America, Larsen had also covered John F Kennedy and Jacqueline Bouvier’s wedding in Newport in 1953.

Life was a window to the world for many Americans. While photo-driven magazines were more common in Europe at the time, Life was the first of its kind in the US. What made Luce’s vision so unique, was that he wanted photos to tell a story, rather than illustrate the words of writers. The photos were central to the magazine’s success, and entire pages were filled with shots, alongside headlines and photo captions (in its early days, photographers were not credited directly beside the photos on the magazine’s pages). This weekly news magazine ran until 1972, then, as a monthly until 2000.

Among the more controversial photos at the time, Martha Holmes, who started shooting for the magazine in 1944, photographed mixed-race crooner Billy Eckstine alongside a gaggle of white female fans in 1950. It was what Holmes considered to tell “what the world should be like”, the photographer once said.

“When that photo was taken, they weren’t sure if they should put it into the issue – a white woman embracing a black man,” said Kushner. “But Luce put it in there because he said: ‘This is what the future is going to be. Run it.’”

When the series of Eckstine were published, the photos garnered vicious letters to the editor, and it was said to have damaged Eckstine’s career. One thing remained. “Luce believed in America and he wanted to tell the stories about it,” said Kushner.

As America’s first picture-driven magazine, it was so popular, people would wait every week to buy the magazine for a dime and look through the photos. “A picture could tell a thousand words, if you could tell how to read it,” she said.

These women were not the first photojournalists. Women began shooting as early as the late 19th century, but that’s another exhibition altogether, one that Kushner could be working on in the future.

For these female photographers, they were just doing their jobs — to get the shot. “When they tried to get a picture, they’d have ten men pushing them out of the way,” said Kushner. “All they were worried about was taking the best photos they could get.”