The French photojournalist Yan Morvan, who has died aged 70 of skin cancer, was a revered war photographer and chronicler of the lives of people on the fringes of society.

He photographed bikers and gangsters in Paris, skinheads and punks in Margaret Thatcher’s Britain, and the exploited sex workers of Bangkok. Though he hated violence, Morvan reported from more than 20 war zones, including Uganda, Mozambique, Kurdistan, Northern Ireland, Rwanda, Kosovo, Ukraine and Lebanon, winning a Robert Capa award and two World Press Photo awards.

His chosen path inevitably led to danger. He was injured numerous times, narrowly escaped a car-bombing, came close to death in Lebanon, and was held under duress for three weeks by the violent gang of Guy Georges – later unmasked as a serial killer – in Paris.

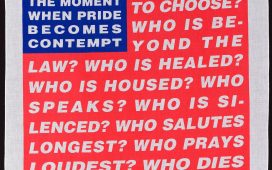

An avid reader of books on philosophy, history and politics, Morvan said: “These are the main subjects of my photographic work.” His oeuvre captures the tragic universality of combat and, by focusing on those living amid catastrophe, the futility and absurdity of war. He wanted to freeze time as only photography can, for future generations to learn from. His desire to educate saw him teach at schools and colleges for most of his life.

In 2004 Morvan began a decade-long project, Battlefields, traversing the globe photographing sites both ancient and modern. “I wanted to address the conscience, to show through landscapes that are sometimes insignificant, a ‘geography’ of human madness.”

His work was published in Newsweek, Paris Matchand Le Figaro, among many others, and exhibited widely, including at the Rencontres d’Arles festival and the Musée de l’Armée in Paris. He also authored some 20 books.

Born in Paris, Yan was the son of Louis Morvan, an engineer, and Denise (nee Reuzeau). His mother took him to Nice at a young age following his parents’ divorce.

There he attended the lycée Masséna, and in his late teenshe moved to Paris with Christine Bolvan, an artist, who would be his life partner. He enrolled at the University of Vincennes in Saint-Denis, Paris 8, to study cinema, but it was the still image that obsessed him. He pored over the French photography magazine Zoom, and imbibed the images of Don McCullin, Larry Burrows and W Eugene Smith.

Morvan dropped out of university, and was broke. He stole to eat, he said, once being chased down the street having pilfered a chicken from a rotisserie; and he stole to pursue his passion: an Olympus camera and lenses from an electronics shop he briefly worked at. He worked sporadically at the photo agency of the newspaper Libération, which published his first picture in 1974, but it was a chance encounter with a biker in Montmartre that kick-started his career.

The rocker introduced him to the Blousons Noir, a youth subculture characterised by the wearing of black leather jackets. Morvan documented the gang’s rebellious, thuggish, rock’n’roll lifestyle for two years. In 1977 he provided the photos for a book about the group, Le Cuir et la Baston (The Leather and the Brawl). When Paris Match subsequently published his biker pictures, the gang members were unhappy with how they were portrayed. They went round to his flat and kicked in the door, his daughter later recalled, but he had moved out.

Morvan began to work regularly for Paris Match. At the end of 1979, he was sent to Bangkok to document the plight of Cambodian refugees fleeing the Khmer Rouge, but that story had moved on, and interest had waned. Morvan saw a different story that needed telling. He befriended the local sex workers and documented their hard lives with empathy and sensitivity for six months.

On his return from Thailand, Morvan joined the SIPA press agency. He immediately left for Turkey, and documented the 1980 coup d’etat. Paris Match published six pages of his work and his life as a war photographer began.

In June 1982, he was sent to Lebanon for Newsweek to record the impact of the Israeli invasion. He became invested in the plight of the inhabitants and covered the conflict until 1985. It was a dangerous assignment for any member of the press, regardless of personal politics, and on two occasions, according to Morvan, he came close to death.

In 1995, while on assignment documenting the underbelly of Paris, Morvan met Georges – who in 1998 confessed to the murder of seven women – in a squat on Rue Didot. Georges and his accomplices coerced Morvan to work for them, photographing them, as well as forcing him to give them money by threatening violence against his family. Eventually, Morvan confided in his partner and the family fled Paris. After the ordeal, Morvan took a two-year break from photography.

In Kosovo in 1999, Morvan saw that there were hundreds of photographers covering the refugees’ every move, and felt he was no longer needed. He was tired of the incessant violence, and decided to take a break from shooting in war zones. In later life he returned to them, and his final two reports came in 2023, first from Ukraine, and then from Israel shortly after the Hamas attacks of 7 October.

Before this return to war zones, Morvan worked on more considered projects. He took portraits of historical battle re-enactors and, after a bad motorcycle accident inspired him, road accident victims. In the project Hexagone (a nickname for France) he criss-crossed his homeland photographing ordinary people and asking what the country meant to them.

Meaning was crucial to Morvan. In an interview in 2017, he said: “Modern man wanted to be immortal. Ancient man wanted to be eternal. Achievements make you eternal, while immortality is something trivial. Finally, it is not immortality that I seek but eternity through my photographs.”

He is survived by Christine, his children, Balthazar, Marie-Yan, Colin and François, and six grandchildren.