In recent years, activists on the left have built a movement for voting-rights restoration. It has largely focussed on the reënfranchisement of people who have already served their time. The legislatures of Kentucky, New Jersey, and Louisiana have restored voting rights for large numbers of formerly incarcerated people; Democratic governors, and occasionally Republican ones, have used their clemency powers to do the same. But these efforts seldom aim for universal suffrage. When advocates in Florida proposed a voting-rights-restoration amendment to the state constitution, in 2018, they excluded people on probation or parole and those who were convicted of murder or sexual offenses. After the amendment passed, with sixty-four per cent of the vote, Republican state legislators passed a bill to lessen its impact, requiring potential voters to pay court-imposed fines and fees before they could cast a ballot. Florida’s Republican governor, Ron DeSantis, signed the bill into law, and, after the Florida Supreme Court affirmed that the law did not contravene the state constitution, he declared, on Twitter, “Voting is a privilege that should not be taken lightly.” (Last week, the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the law violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, upholding a federal judge’s preliminary injunction.) Many people—including Hillary Clinton, who supports voting rights for former but not current prisoners—tweeted back at DeSantis to say that voting is not a privilege but a right. DeSantis later blamed his staff for the tweet.

Americans generally assume that they have a right to vote, but that right is not explicitly guaranteed by the Constitution. Voting isn’t mentioned at all in the Bill of Rights; the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, which were adopted shortly after the Civil War, refer to a right to vote, and there are legal scholars who believe that this implicit granting of the right applies to all citizens. But the Supreme Court has continued to defer to states when it comes to the regulation of elections—a legacy, in part, of the original drafting of the Constitution. In 2013, when the Supreme Court overturned a key provision in the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Chief Justice John Roberts, who wrote the decision, cited an earlier ruling, which held that “the Framers of the Constitution intended the States to keep for themselves, as provided in the Tenth Amendment, the power to regulate elections.” As Victoria Bassetti, a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice, has observed, it was not “politically practicable,” when the Constitution was written, “to impose uniform suffrage laws across the former colonies. Was the fragile new federal government really going to tell South Carolina that free blacks could vote? Or was it going to have to do the opposite and tell Massachusetts, which did allow blacks to vote, that it would have to stop? Easier to let state laws and provisions dealing with the vote stand.”

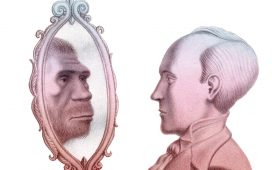

Two centuries ago, only Connecticut barred citizens with criminal convictions from voting. The state’s constitution, which was ratified in 1818, declared that a man’s right to vote could be “forfeited by a conviction of bribery, forgery, perjury, duelling, fraudulent bankruptcy, theft, or other offence for which an infamous punishment is inflicted.” In the years before the Civil War, seventeen states joined Connecticut in passing some form of felony disenfranchisement. Then, in the decade after the abolition of slavery, while the national movement for black suffrage was building momentum, ten more states, mostly in the South, quickly adopted them. The same period saw a sharp increase, in many states, in the incarceration of African-Americans. (Although the vast majority of people in prison cannot vote, the census counts them as living where they are incarcerated, shifting political representation to the places that have prisons.)

Many state lawmakers were explicit about the racist motivations for these changes. In 1901, Alabama Democrats, who had a history of election tampering, called a convention to rewrite the state constitution. “The justification for whatever manipulation of the ballot box that has occurred in this State has been the menace of negro domination,” John B. Knox, the president of the convention, said in his opening remarks. “If we should have white supremacy, we must establish it by law—not by force or fraud.” The resulting constitution named twenty convictions, from robbery to forgery to vagrancy, that would strip men of their right to vote. The same document discriminated against black voters with poll taxes and literacy tests.

Felony-disenfranchisement laws spread across the country: by the nineteen-seventies, forty-six states had them. Massachusetts was the last state to join the group, passing a constitutional amendment in 2000 with more than sixty per cent of the vote. (The Prison Policy Initiative observed that it was “the first time that the Massachusetts constitution has been amended to take away rights from a group of people.”) Three years later, three researchers published a paper in the American Journal of Sociology showing that the most stringent of these laws were to be found in states with many potential voters of color. In Tennessee, where citizens lose the franchise for life if they are convicted of crimes such as forgery, sodomy, or receiving stolen property, a fifth of African-Americans are barred from voting, according to the Sentencing Project. (The same was true in Virginia and Alabama until recently, when the Democratic governors of those states restored the franchise to large numbers of citizens.)

Vermont and Maine, the only states that have never disenfranchised prisoners, are also the whitest states in the nation. Less than four per cent of Vermonters, and less than five per cent of Mainers, are people of color. “I do think that it’s not a coincidence that it’s only Maine and Vermont that allow inmate voting,” Emily Tredeau, a supervising attorney at the Vermont Prisoners’ Rights Office, told me. “White voters will give pause before they disenfranchise other white people.” Joseph Jackson, a formerly incarcerated activist, added, “Mainers look at Maine folks that are incarcerated as though they are not other.” (While the prison population in Maine is mostly white, it is significantly less white than the state as a whole: nearly twenty per cent of those incarcerated in Maine are people of color.)

Maine has not been entirely immune from peer pressure, though: between 1999 and 2013, legislators in Maine proposed bills to restrict voting from prison on six different occasions. L. Gary Knight, a Republican former member of the Maine House of Representatives, led the last of these efforts. He recalled that several people had been murdered in his area of Maine, and after speaking to the families of the victims, he was disturbed that those responsible were still allowed to vote. “I wondered why they could still be having some of the privileges of citizenship while they were incarcerated,” he told me. “I put the bill in to bring us more into line with what the rest of the country was doing.” He saw his proposal as a relatively moderate measure: it only would have affected people serving long sentences, most of whom have committed serious crimes, such as murder or rape. (The restrictions, under his proposed law, would have been lifted when people completed those sentences.) “It was deliberate that I did not try to involve all prisoners,” Knight told me. People with criminal convictions should not be able to vote for judges who decide criminal cases, Knight thought. “When you break laws, there are consequences to those laws. Of course they should give up their rights.”

Knight’s bill was opposed by a broad coalition, including the A.C.L.U. of Maine, the Maine N.A.A.C.P., and the Maine Council of Churches. Laurent Gilbert, a former police chief and the mayor of Lewiston, denounced it, saying that “maintaining the dignity of the human being is of utmost importance for a person to accept responsibility for his or her actions.” Rachel Talbot Ross, a prison abolitionist who, as the president of the N.A.A.C.P. of Greater Portland, organized voter-registration drives in prison, said, “We cannot conscionably penalize entire communities by reducing their political power and their voice in the political decisions that affect them.” Democrats in the legislature defeated the amendment by a wide margin. Three years later, Talbot Ross became the first African-American woman elected to the Maine House of Representatives.