Highlights

- Video games can be a form of art that explores deep themes, such as mental health, politics, and the human condition.

- Some games aim to promote empathy through gameplay and moral choices.

- Games like Shadow of the Colossus show how traditional gameplay and player interaction can create a transcendent experience.

In 2010, Roger Ebert wrote a famous essay in which he declared that video games could never be art. Games are, in today’s world, primarily viewed as products designed to draw quarters (or, by today’s standards, $70 plus DLC), a notion that could convincingly move critics to the position that they are mere products, toys, or novelties. However, a prospective filmgoer back in 1878 who had only ever seen Eadweard Muybridge’s The Horse in Motion might be inclined to condemn cinema the same way Ebert did of video games. Like movies or the product of any other artistic discipline, games have had their fair share of trial runs or all-out empty vessels.

6 Games That Are Surprisingly Thought-Provoking

These games may not immediately strike players as philosophically deep, but they do have many thought-provoking themes.

The several decades of being almost exclusively marketed to hormonal young boys certainly haven’t helped their legitimacy in the eyes of critics and academics, to say the least. However, despite lacking an institution to canonize them and despite being subjected to ever-increasing overfinancialization at the cost of creative freedom, great works in the medium persist nonetheless. A true work of high art, light or dark, absurd or straight-faced, punctures beyond the gossamer of the ordinary and speaks directly to its finder’s soul, transporting its holder into a spiritual plenum, a vantage from which to snatch life’s true meaning, perhaps even moving them enough to change their mind.

Disco Elysium

A Materialist Investigation Of The Human Animal (From Rock-Bottom Up)

Disco Elysium

- Released

- October 15, 2019

- Developer(s)

- ZA/UM

-

Disco Elysium

provides a profound exploration of existential and political themes through RPG conventions and mechanics - ZA/UM proves that video games can contain mature, meaningful discussions about mental health, economic systems, and the human condition

A poet might say that art can be found anywhere in nature, in the human world, even in nothingness. Disco Elysium is not a game that can be interpreted as art, nor was it found that way; it was built from the ground up as such, and by ZA-UM, a bonafide art collective, no less. A work of art’s legitimacy does not necessarily stem from its author’s credentials, but in this case, the work speaks volumes about its masteries. Even with its mesmerizing oil-painterly art style, music and sound design, and stunningly frank, darkly sublime writing, DE is more than the sum of its parts. It crosses fearlessly from the political to the existential without its profundity overstaying its welcome for a moment, thanks to an expertly measured amount of self-awareness, humor, and a strictly high bar for quality.

ZA/UM expertly took elements of the role-playing game genre and used them to draw up the absurdity of living as a human animal under incomprehensibly vaster cosmic and economic forces. Few games have managed to maturely explore the territory of the human mind and mental illness quite as well as Disco Elysium. Despite all this, it is an immediately accessible game, complete with all the gameplay mechanics expected of a classical RPG (minus the combat system). The outcome of skill checks is never “win or lose,” just as each character in Revachol (including the protagonist) is not overlooked for their personal, economic, or situational shortcomings. On the contrary, their characterizations are able to speak directly to the player’s own lived experiences, existential fears, and secret hopes.

Special mention: Senua’s Sacrifice

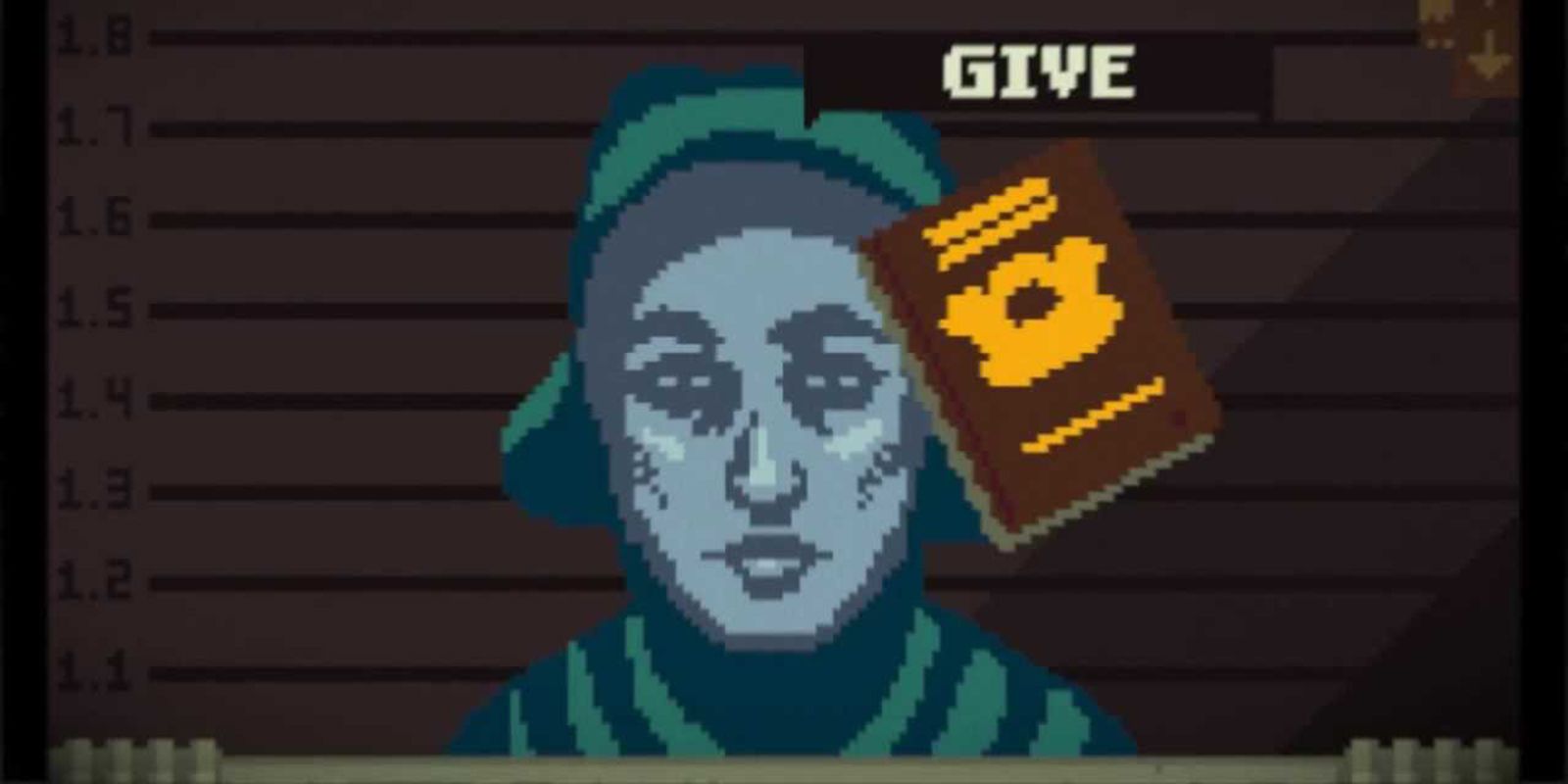

Papers, Please

The Rise Of The Empathy Game

Papers, Please

- Released

- August 8, 2013

- Developer(s)

- 3909 LLC

- Genre(s)

- Simulation

- This bureaucracy simulator puts the player in the unusual shoes of an immigration officer, forcing them to make uncomfortable and compelling moral choices

-

Papers, Please

helped kickstart an entire genre of games that aim to increase empathy in its players

Kill or be killed is just about the easiest feature to code in video games, and it’s the driving throughline through practically every popular title on digital storefronts these days. However, rather than dedicating half a decade’s worth of production time to creating the most visceral, money-making eye candy for some twitchy trigger time fun, some developers have chosen to use their tools to promote empathy. This game is a stellar example of a game that leverages its mechanics to do so in a “play-don’t-tell” manner. In Papers, Please, players find themselves in the unusual role of an immigration inspector at the border of a country.

10 Games With Profound Morality Systems

While most games allow players to do what they please, some games have morality systems that could alter the gameplay entirely, like these examples.

Rather than simply assuming this role as the usual disembodied hand and camera, they have several resources to manage, ranging from the hunger of their family to the stability and security of their country. Watching someone experience a moral dilemma is much different from experiencing one, albeit simulated, and Papers, Please proves this from the very moment the game starts until the end by throwing crisis after compelling crisis on the player’s desk. Although many critics have said that video games are responsible for desensitization thanks to their typically violent gameplay loops and high levels of graphical realism, a whole movement has arisen around promoting empathy through gameplay since Papers, Please‘s release.

Special mention: This War of Mine

Shadow of the Colossus

A Stripped-Back Minimalist Masterwork

Shadow of the Colossus

- Released

- October 18, 2005

- Genre(s)

- Adventure

-

Shadow of the Colossus

proves the artistic caliber of the medium without having a reliance on novelty or innovative programming - While it implements a minimal amount of dialogue and cutscenes, this game evokes emotion through its gameplay and long-term input and interaction

By most metrics, Shadow of the Colossus is a very traditional game. There is a storyline, bosses, health mechanics, and an ending. The game is captivatingly beautiful, but it would be hard to argue that no other title has matched its fidelity, especially in recent years. It may not have created a new genre or become self-aware, but it is one of the most concise examples of how a combination of tightly focused gameplay and player input can produce a transcendent experience impossible to find in other mediums, infused with notes of terror, triumph, dedication, and guilt, to name but a few.

Of course, many games achieve the same effect, but none are quite as streamlined and focused as Shadow of the Colossus. Those skeptical of non-linear games due to their “loss of authorship,” or those who demand any artwork to prove an artist’s “intention” may at least compromise with a game so stripped back, awaiting only the secondary author, the player, to deliver the inputs to bring it to its sobering completion. The beauty of this contender as a work of art is that it proves that while video games can be infinitely creative and mechanically surprising, they are fully capable of achieving masterwork status even on their own most basic terms.

Special mention: Spec Ops: The Line

Undertale

When Art Gains Self-Awareness

Undertale

- Released

- September 15, 2015

- Developer(s)

- Toby Fox

-

Some critics consider art disciplines mature when they become self-aware, and

Undertale

exemplifies this evolution effortlessly -

Undertale

has the player question morality and violence, agency and choice, and can disarmingly remind them of the beauty of life

Just as with plays, novels, and cinema, all art disciplines go through a transition into self-awareness and deconstruction. This marks the moment of maturity, when it begins to recognize its own language and history, breaking them down in a fit of self-awareness. No other game demonstrates this feature quite like Undertale, which appears on the surface to be a loving homage to 16-bit era games of the past. However, those who have experienced it from start to finish to its “true end” will understand that the relationship between player and game is more than parodied, examined, or mastered (although it does all three).

10 RPG Games With Surreal And Dreamlike Worlds

Players will dive into a breathtaking RPG world with these surreal landscapes and dreamlike settings.

Undertail disarmingly challenges a player’s notion of game grammar in its questioning of violence, but more, it masterfully evokes profound doubts in the player’s mind about their expectations of “choices.” Other “artful” games have tackled the concept, but Undertale creator Toby Fox somehow managed to use the medium itself to break the player’s inherent time-traveling, save-loading powers to dramatic and striking effect. Once the player reaches a certain point in the branching story, they may find themselves reaching to peep back to “consume” more “content,” but they may find Undertale itself staring back.

Special mention: The Stanley Parable

Dwarf Fortress

The Sublimity Of The Code

Dwarf Fortress

- Platform(s)

- Linux , macOS , Microsoft Windows

- Released

- August 8, 2006

- Developer

- Bay 12 Games, Tarn Adams, Zach Adams

- Genre(s)

- Roguelike , Strategy , Simulation

-

While many games claim “artful” status via their visual fidelity or cinematography,

Dwarf Fortress

proves that a work of art’s magic can be found in its code - The sheer scale of the simulation is awe-inspiring and can be appreciated not for its “win or lose” outcomes but for its unbound potential

Some games are said to be interactive forms of art. While some titles offer such visual spectacle that they would handily fall into the category in their own right purely from a painterly perspective, others borrow so heavily from other disciplines like cinema that they end up being more like “playable movies” that would no doubt garner encouragement from film or critics who snub video games as toys. However, critics rating a game on its visuals or cinematography alone somewhat fail to grasp what the spiritual core of the video game really is: agency in play. Visually crunchy games like Dwarf Fortress demonstrate its artfulness in its lines of code.

Video game skeptic Roger Ebert said in his critique of the medium, “One obvious difference between art and games is that you can win a game.” As Dwarf Fortress was designed to be more of a universe simulator, the game can’t technically be won or lost, only experienced as a complete cosmos in and of itself (or as complete as one can be on a contemporary computer). There is no middle, beginning, or end. There are richly simulated Dwarves and the richly interconnected world around them that, in tandem, reflect a pure act of creation. While they come with limits (as any work does), Dwarf Fortress and its first-person cousin have punched holes in the possible.

Special mentions: Minecraft, Infiniminer

8 Games With Complex Ecosystems

Like nature itself, these games have deep and ambitious ecosystems.