Olympic test events are supposed to be just that — a litmus test for Olympic hopefuls, the host city, and the international sports federations responsible for the competitions.

This summer’s events in Tokyo have mostly been a test of how to manage the heat. On Thursday, the women’s triathlon was shortened because of dangerous temperatures.

Tokyo officials had already added extra water stations and positioned medical personnel every 500 meters on the run course, added more air-conditioned areas for athletes before and after the race, and set up massive ice baths for competitors past the finish line.

But the heat forecast was extreme — too extreme for a full-length competition.

At 3:30 in the morning, representatives and delegates met to measure the water quality, water temperature and weather forecast for the day ahead. The meeting was not out of the ordinary. Water temperatures and quality must be tested to ensure the safety of the athletes, according to the rules of the International Triathlon Union, the sport’s world governing body.

The water quality was within the acceptable limits. The water temperature was 86 degrees Fahrenheit, just below what could be deemed too warm to compete, a threshold set at 89 degrees.

But the Heat Stress Indicator, which takes temperature, humidity, wind speed, sun angle and cloud cover into account, would move to a level considered dangerous by the end of the run. So the committee decided to cut the run segment in half, from 10 kilometers to 5 kilometers.

Less than three hours before the start of the race, athletes and coaches received an email with the subject line: “URGENT MEMO: Change of the run distance in the Elite Women’s race.”

The event was supposed to be the first auto-selection opportunity for many triathletes, meaning a top finish that met the qualifying standards would result in a spot on an Olympic team for certain countries, including the United States.

That meant an immediate change in strategy for athletes who trained for an Olympic distance of the triathlon — a 1,500-meter swim, 40-kilometer cycling segment, and a 10-kilometer run. Those who usually excel in the running segment would have to make up time in the swim and bike portions of the race.

For some delegations, Australia among them, the change in format voided the automatic Olympic qualifying process. The event remained an auto-selection opportunity for U.S. athletes despite the change.

John Farra, the high performance general manager at USA Triathlon, said the athletes were expected to adjust accordingly, “No one would want a change in plans,” he said in a phone interview ahead of the women’s start. “But it’s still going to feel as close as we can get to a test of the Olympic experience.”

Ultimately, Summer Rappaport, who was not considered a shoo-in for the United States, finished fifth in the race. Rappaport, 28, finished the shortened course in 1 hour 41 minutes 25 seconds. Katie Zaferes, a favorite for the Olympic podium, did not automatically qualify after being involved in a bike crash. Her next opportunity to auto-qualify is in May 2020.

The triathlon at the Olympics next year could be cut short, too, Farra noted, since organizers will always veer on the side of caution to protect the athletes.

Friday morning, when the men’s triathlon event was scheduled, another email was sent out with a more celebratory tone. “URGENT MEMO: No changes in the Elite Men’s race,” it read. Temperatures were expected to be hot, but in the moderate to high range according to the forecast.

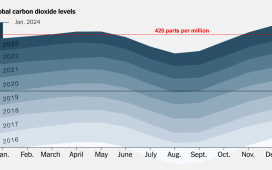

Summers have become increasingly hot in Tokyo. In 2007, Japan’s meteorological agency created a new term to mark any day above 95 degrees: “Ferociously Hot Days.”

In preparation for the 2020 Olympics, the city has repaved more than 100 kilometers of roads around Tokyo with a reflective material that is supposed to reduce heat. They have installed misting fans, cooling areas, and are passing out ice packs to spectators, volunteers and athletes.

But those measures can only make conditions so comfortable.

During a beach volleyball test event in late July, athletes sat in giant buckets of ice water as organizers sprayed the sand with hoses. Four people still required medical attention.

A few weeks later, in a rowing test event, three athletes were treated for apparent heat exhaustion. The temperature at the rowing test event was recorded as 93 degrees Fahrenheit despite starting before 10 a.m.

The Tokyo Olympics will not be the first to require athletes to adapt to extreme temperatures.

At the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, athletes taped their faces to avoid frostbite. At the 2004 Athens Olympics, Meb Keflezighi and Deena Kastor both famously wore ice vests until the last possible moment before winning silver and bronze medals in the Olympic marathon.

This may be the new normal. The 2024 Olympics will be held in Paris, which experienced its hottest day on record this July, with temperatures nearing 110 degrees.