In Geoffrey Chaucer’s England, the arrival of spring was taken by many as a cue to take to the road. As the prologue to The Canterbury Tales begins: “When in April the sweet showers fall/And pierce the drought of March to the root, and all/…Then people long to go on pilgrimages”.

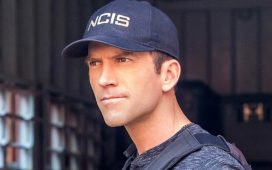

Given Britain’s increasingly damp climate, contemporary pilgrims are as likely to encounter persistent rain as the occasional sweet shower. But the participants in the BBC’s sixth Pilgrimage series, which ended on Friday, were largely blessed with fine days as they travelled by foot and bus across North Wales. Travelling the Pilgrim’s Way, the group of minor celebrities followed a Christianity-based route-map of shrines and churches, but also stayed at an eco retreat and a Buddhist meditation centre.

Including on this occasion a lapsed Muslim comic, and a star from the first series of Traitors, this was unusual reality television. No one is voted off Pilgrimage and the ethos is collegiate rather than competitive. That in itself is refreshing. But the show’s long-running success also testifies to the popularity of an activity that has undergone a remarkable 21st-century renaissance. This spring, thousands of Britons will join walkers from around the world on the Camino de Santiago, the most famous Christian pilgrimage route of all. In the early 1980s, the numbers completing the Camino were in the early hundreds; last year a record 446,000 did enough to earn an official certificate. Across the rest of Europe, trails are being reopened.

There is no single explanation for the phenomenon. Many of those on the move will not belong to any church. One Spanish study of Camino walkers between 2007 and 2010 found that 28% – easily the biggest category – said they were there for spiritual reasons, which will mean different things to different people. Some pilgrims may be hiking for charity, and some to leave a dark period in their lives behind. Others may go in memory of a loved one, or for the glories of the landscape, or to clear their minds.

Given the growing numbers, something is working. To undertake a journey can be both clarifying and transformative. Thresholds are crossed, literally and figuratively. In David Lodge’s 1990s novel Therapy, a character on the Camino who recently lost her son says she needed “something quite challenging and defined, something that would occupy your whole self, body and soul”. In North Wales, some of the BBC’s Pilgrimage participants movingly found solace in working – and walking – through the pain of bereavement and loss.

The world’s major religious traditions, which all place a high value on pilgrimage, have long understood this dynamic. In the secularised west, the current revival suggests that spiritual journeying will comfortably survive the decline of churchgoing. The practice has, after all, outlived more direct threats in the past. The springtime expeditions that Chaucer depicted were suppressed in 1538 by Henry VIII’s consigliere, Thomas Cromwell, who viewed pilgrimage as a form of idolatrous superstition. Five centuries later, that argument hasn’t aged well.