The bio-pic is a genre of extremes. The best ones share a uniquely powerful artistic authority, but merely ordinary ones are truly disheartening. The trouble isn’t only that of inflated prestige; bio-pics are disproportionately prominent during awards season and therefore ballyhooed nearly to oblivion. The form’s peculiar place in the art of movies is inseparable from the reasons for its exceptional prominence in the business. For producers and studios considering which projects to green-light, bio-pics check a lot of boxes. The protagonists are people who audiences are already familiar with and interested in. (J. Robert Oppenheimer may be the exception that proves the rule; he’s less famous than Freddie Mercury, but the atomic bomb is more so.) And the illustrious people who inspire bio-pics offer great showcases for actors. That attracts stars, which in turn attracts audiences. Bio-pics bathe the producers, the studios, and the filmmakers in the reflected renown of their protagonists’ achievements, and, because the enterprise inherently involves a good deal of research, it also conveys an air of studious seriousness. Presenting real-life stories as extraordinary adventures, bio-pics embody the axiom that truth is stranger than fiction. (Fear not: by the time Hollywood gets done with these lives, they’re rarely any stranger than the usual fictions, and may not even be that true.)

Nonetheless, the connection of bio-pics to ostensible reality is the hidden power of their success. If the makers of bio-pics freely elaborate (i.e., distort, bowdlerize, even falsify) the facts of their heroes’ lives, they don’t do so any more than the average Hollywood movie falsifies human experience at large, but they do so with an imprimatur of authenticity. With all the overt and tacit calculation that goes into the production of bio-pics, it’s something of a miracle that any of them are any good at all, yet indeed some of them are even great.

Perhaps the hardest thing about making bio-pics, at least ones regarding figures of actual greatness, is the inability of most directors to consider such heroes face to face, to share in the grandeur or the enormity of these protagonists’ inner lives. I’m reminded of an aphorism that I have long recalled as being written or said by Norman Mailer—please crowdsource me—to the effect that the one kind of character that no novelist can successfully imagine is a better novelist. I suspect that this inability, for novelists (and for filmmakers), goes beyond the limits of the artistic sphere to extend, over all, to exemplary achievers in any field. Most directors, like most people, have interesting observations about their daily lives, their communities, their fields of endeavor—and plenty of directors have, as artists, the practical skill to convey such observations. Part of the long-standing collective lament for the demise of the mid-budget dramatic movie—essentially, realistic movies featuring movie stars—is that it’s a form that even middling directors, writers, and actors have always done well. But bio-pics are different, because they are about extraordinary people, and fewer directors, writers, and actors are able to successfully imagine their way into this level of extraordinariness. The genre poses challenges of scope and psychology akin to the stringent visual challenges posed by musicals. Unlike with melodramas or comedies, it takes greatness to advance the art of bio-pics. The list that follows is thus also a parade of great directors.

It’s fascinating to see which great directors have chosen to make bio-pics (whether one as an exception or many as a habit) and what that choice reveals of their art. For instance, it’s no surprise that the history-obsessed John Ford made a bunch of excellent ones and that the extravagantly inventive Howard Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock did hardly any. It’s similarly logical that Kenji Mizoguchi, a relentless analyst of Japanese history, would make several, and that Yasujirō Ozu, mainly a storyteller of modern family lives, would make none. But it’s surprising that Satyajit Ray, whose films ranged widely through Indian history and society, didn’t make any, and equally surprising that Max Ophüls, an artist of ironic spectacle, did so to great effect; fascinatingly, in Ophüls’s vision of life as inherently a matter of theatrical pretense, the gap between fact (theatricalized) and fiction (exposed) closes. For Abbas Kiarostami, a real life based on falsehood proves an ideal laboratory for the fusion of fact and fiction. For urban folklorists and analysts (such as Spike Lee, Martin Scorsese, and Raoul Walsh) and for autobiographical portraitists and historians of style (such as Terence Davies and Sofia Coppola), the lives of others are naturally linked to first-person observations and modes of expression. For all these filmmakers, the project of bringing to life a person who has already lived means a confrontation not just with the particularities of that one individual but with the nature of personality—of character and human behavior—itself.

In compiling the list, I’ve set a few ground rules for myself: first, no approximations, only characters bearing the names of people who existed and did pretty much what’s seen in the movie. (In other words, no 1932 “Scarface,” however closely the character of Tony Camonte is based on Al Capone, and no “Citizen Kane,” which owes much to the life of William Randolph Hearst.) Also, I’ve avoided movies that are not centered on the life of a single character, even if they are based on true stories, such as “Zodiac”; there’s a difference, imprecise but meaningful, between a bio-pic and a historical drama. Moreover, no more than one film per director. I’m presenting these titles in chronological order, and, though I hope that you’ll get to see all of them in some way or another, I’ve selected them without regard to their current availability, whether streaming or on physical media.

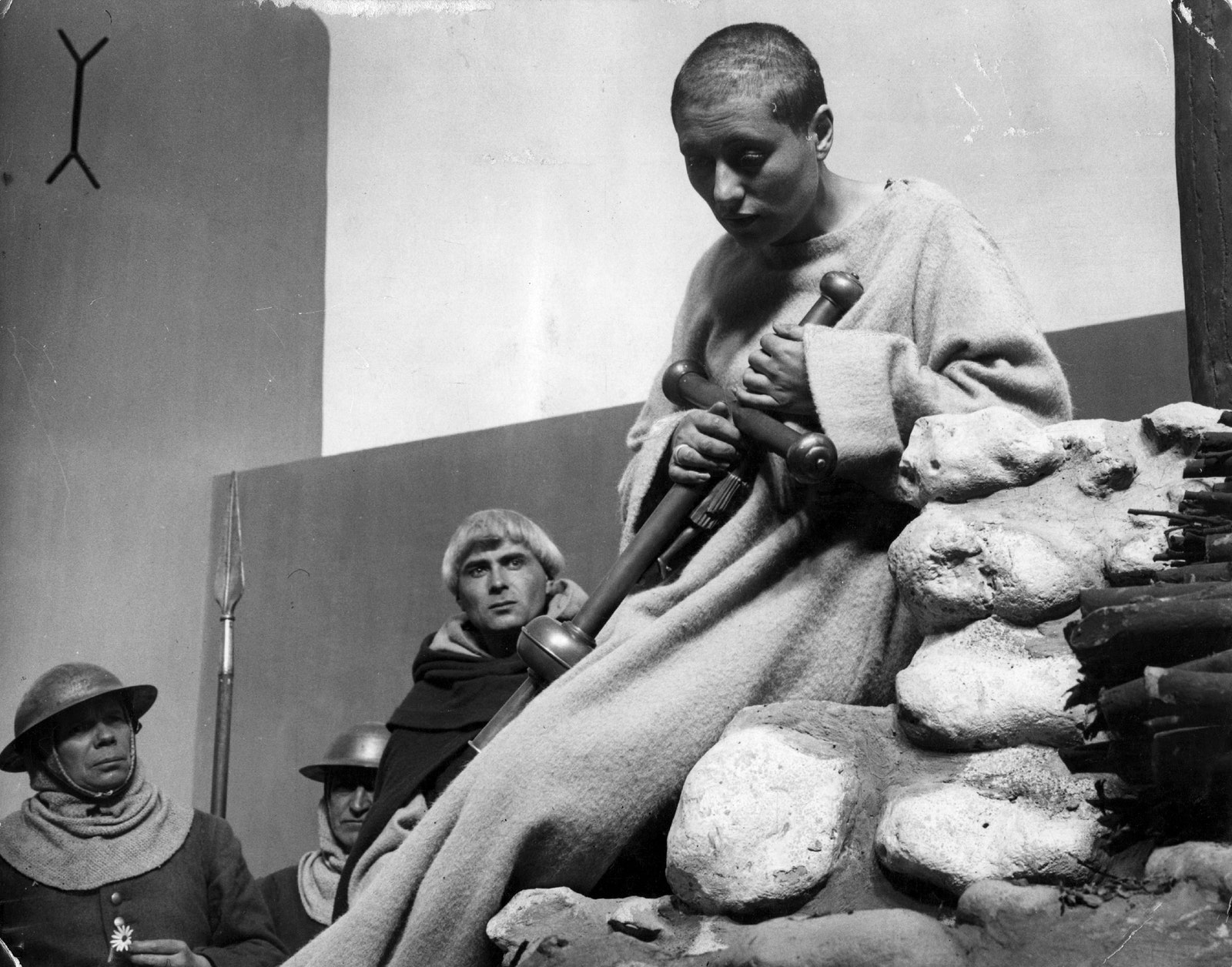

Photograph from Henry Guttmann Collection / Getty

“The Passion of Joan of Arc” (1928, Carl Theodor Dreyer)

Ernst Lubitsch may have perfected the evocation of sound and music in silent films, but Dreyer, in this movie based on the trial transcripts of the medieval French national heroine, brings silent-film dialogue to its artistic pinnacle. The stark intensity of his images and the expressive clarity of the lead performance, by Maria Falconetti, give birth to an instantly avant-garde cinema that’s also a synthesis of the classical arts—a literary tragedy realized with the torque of theatrical artifice and a painter’s precision.

Errol Flynn has a rollicking good time portraying the boxer James J. Corbett, who rose to fame in the late nineteenth century for being as dashing and witty outside the ring as he was suavely powerful inside it. A poor San Francisco bank clerk and the son of a coachman, the amateur pugilist Corbett talks his way into high society at the moment that high society wants to render the low-life spectacle of prize-fighting respectable. The effervescent story tracks the brashly elegant boxer’s progress from waterfront brawls to the heavyweight championship—by way of the balletic footwork that was his signature maneuver—his courtship of a free-spirited heiress (Alexis Smith), and his surprising side business portraying himself onstage. Walsh—born in 1887, the year the action begins—films rowdy times rowdily, delighting in the teeming cast’s gimcrack manners and in the raffish early days of the modern sports business.

“The Great Moment” (1944, Preston Sturges)

The madcap champion of motormouth comedies seemingly veers weirdly off-course in dramatizing the career of the mid-nineteenth-century dentist named William Morton (played by the gruffly folksy Joel McCrea), who, despite opposition from doctors, pioneered the use of ether as an anesthetic. Amazingly, Sturges nonetheless presents the tale as a kind of screwball comedy, albeit one whose antics serve up a strong dose of homespun philosophy: The surprisingly far-reaching point is that so much of what matters in the world at large is the work of boastful dreamers with swollen heads, empty pockets, and fast-talking chutzpah; so much of what makes life sweet, or even bearable, comes from out of left field, by way of crazy coincidences that make screwball comedies feel like documentaries.