The opening works of Small World, the latest Taipei Biennial, which closed on Sunday, are as pointed as the gently provocative exhibition ever gets: first a section featuring the pioneering Palestinian digital artist Samia Halaby, then a wall of photographs by Hsu Tsun-Hsu documenting Taiwan’s transition from military dictatorship in the 1990s to thriving democracy.

Co-curated by the Beirut-based Palestinian curator Reem Shadid, the Hong Kong-based Taiwanese curator Freya Chou and the New York-based Taiwanese American writer Brian Kuan Wood, Small World applies the perspectives of very small but embattled places, like Taiwan and Palestine, to big questions of humanity, safety and community.

“There were no structural changes after [Hamas’s attack on Israel on] 7 October, just a number of impassioned statements during the opening days, and impassioned discussions,” Kuan Wood says. “The original show stands up; we are the same curators as before. We did worry, as Reem is Palestinian, the sort of attention that might generate,” but the ensuing local reaction “has been wonderful”.

“After we started planning, the world changed,” says Jun-Jieh Wang, the director of the government-backed Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM). It has hosted the Taipei Biennial since 1992, making it the oldest in East Asia and one of the first in the whole Asian region. TFAM last year celebrated its 40th year, and a new wing expanding upon its original premises is nearing completion.

The biennial, Wang says, “is superficially apolitical, about how the pandemic has changed life afterwards, globally. There are different kinds of political: some contemplative, not critical.”

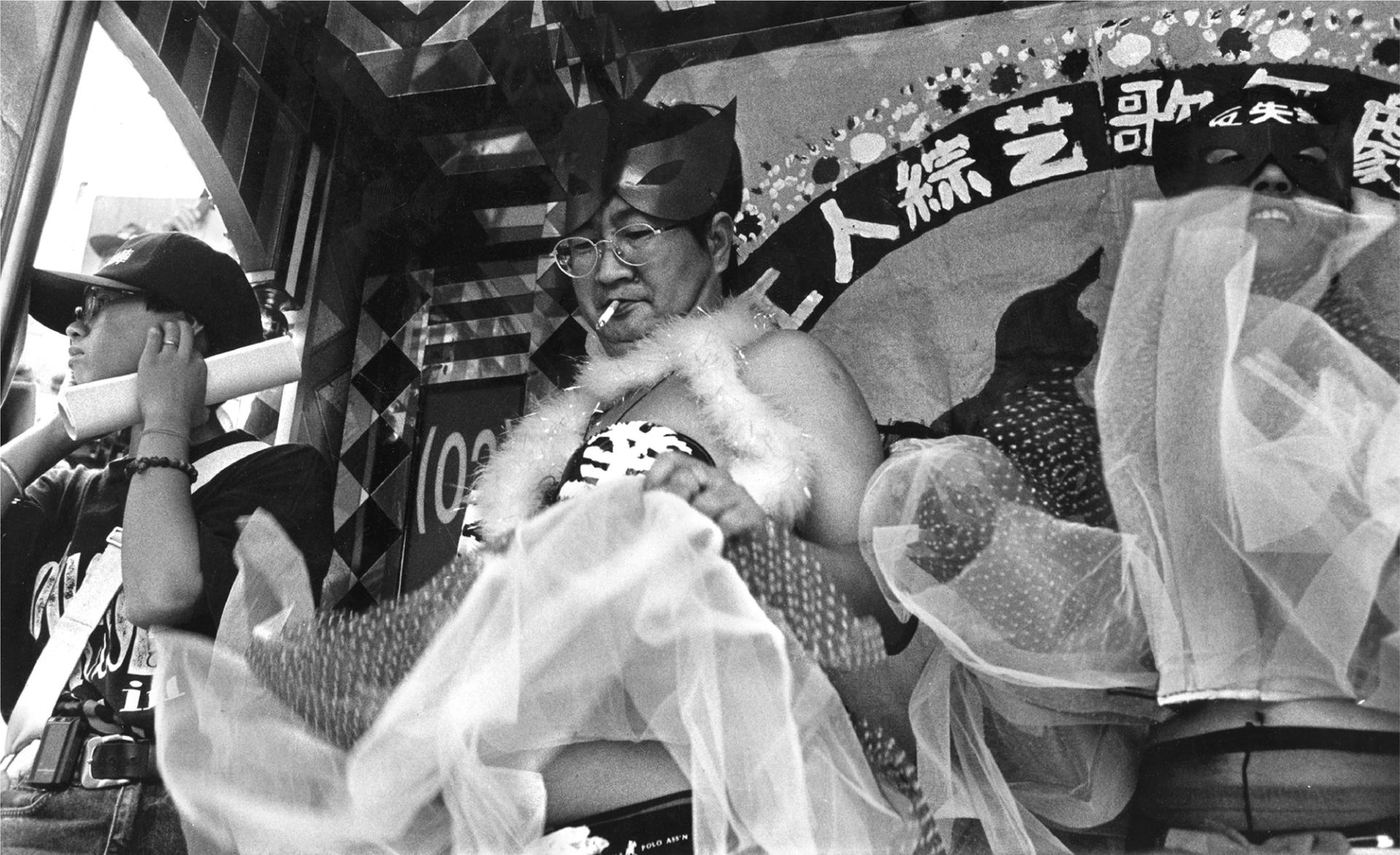

Hsu Tsun-Hsu, The More We Get Together: The Annual Autumn Worker’s Struggle (1996) Courtesy of the artist

Hsu’s historic photographs cover a deep green wall, a veiled reference to Taiwanese politics—the recently re-elected Taiwan Progressive Party is shorthanded green to the opposition’s blue—that organisers would neither confirm nor deny.

“People would rather forget [the pandemic], it was very painful, but we are seriously overdue for some self-examination. With the understandable urge for the ‘normal’, still we must have learned something,” Kuan Wood suggests.

Time for transparency

An unapologetically unambiguous contemplation of disease, lockdowns and loss, Small World posits a need for openness, transparency and honesty in moving forward. In a period of “extreme confrontation”, the show “deflects the geopolitical in a sense, translating it into the mundane, private and painful,” Kuan Wood says. Amid “this divisive political condition, we find the place of complexity.” Covid “fragmented the social fabric but brought the world together in a strange confinement, a scramble to say alive.” Rather like how Covid particles can decimate a host’s body long after an acute infection, the whole world seems to have political long Covid. Fissures predating the pandemic have only deepened since. Yet our shared trauma could provide a starting point for empathy.

Atomisation amid closeness took form in the popular favourite The Wall: Asian (Un)Real Estate Project (2023) by Aditya Novali, miniaturising Asia’s massive apartment towers and imagining the madnesses percolated by being locked inside them—though he planned the piece pre-pandemic. The Indonesian artist’s background in architecture and shadow puppetry shows in the theatricality of each tiny room’s particular tableaux, from the silly to the gory to the kinky.

Nadim Abbas, Pilgrim in the Microworld (2023) Courtesy of the artist and Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Next to it, in the final first-floor hall, Hongkonger Nadim Abbas’s installation Pilgrim in the Microworld (2023) inverts the diorama with a room-sized sandbox microchip, that symbol and supposed security shield of Taiwan. Rendered in steel and sand and reconfigured daily, they upend that sense of permanence, of security as well as of our known conditions.

The surrounding walls reinforce—or deinforce—with Paul Virilio’s Bunker Archeology (1958-65). Ghostly pictures of decaying Nazi bunkers along the coastline of his native France, some embedded into sand dunes, they highlight the impermanence of regimes and the futility of defensive European identities. Only the facing, implacable ocean persists.

Paul Virilio, Bunker Archeology (1958-1965) Courtesy of Sophie Virilio and Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Jen Liu delves under the waves in the fantastical allegory The Land at the Bottom of the Sea (2023), which is the final part of her long-running film series Pink Slime Caesar Shift. The disappearance of female migrant South Chinese labour activists is turned into a literal liquidation, making them into underwater beings and finding some beauty and hope against a world in which their political or financial survival was always so improbable.

Philosophical dilemmas

Kuan Wood suggests that the prevalent “American influence in the world is in the water, in the air. You see the specificity of that divide in many parts of the world, the doom-scrollers of the earth. It becomes more and more common, enmeshed in the technology. There are so many divisive conditions, across the world, that share a political bankruptcy. There is a need for attention, not agency or belief, in this absence of traditional politics: the Covid toxicity.”

The video What is Your Favorite Primitive takes fantasy in a compellingly cynical direction, as the Taipei-based Taiwanese artist Li Yi-Fan puts his absurdist, digitally rendered characters through violent confrontations and philosophical dilemmas. Just as how screens can bring out human cruelty through anonymity, a godlike Li turns his cursor into a sort of vindictive empowerment.

An entire hall is filled with Jacqueline Kiyomi Gork’s Not Exactly B Flat (2017), inflating and collapsing columns and walls like a giant’s lungs or the ebbs of time. The half-dark, cold space is overwhelming as it wheezes, simultaneously comforting and unsettling. Sound and music receive particular emphasis in Small World, with inclusions like DJ Sniff and several local indie labels, partly in recognition of how musicians and other performers were the creatives who struggled most during the pandemic, Kuan says. As more grassroots artists, “Musicians are out of place, and not respected in institutions.”

Doubly ostracised are migrant musicians, and a January-long interaction helmed by Julian Abraham “Togar” and Wok the Rock showcased Indonesian musicians in Taiwan. “There is a very vibrant migrant music community here, like an underground volcano about to explode,” Kuan Wood says, mixing Indonesia’s rich musical history with Taiwan’s.

Karen Mok, a Hong Kong pop star who also has Persian heritage, provides audio for the sound installation Watershed (2023) by the Berlin-based Iranian artist Natascha Sadr Haghighian. In TFAM’s garden atrium, effervescent blobs in walkers warble forth Mok’s 1999 ballad Suddenly, intended in tribute to how caregivers often lose their sense of self in their undersung role. The song intermingles with the frequent low-buzzing plane to or from nearby Songshan airport, promising a bigger world possible even to those, like caregivers, or the pandemic isolated, currently trapped in smaller confines. Or that better times could follow today’s vicissitudes.