It takes a little over two hours to drive from Multan, a city in southern Punjab, Pakistan, to the village of Shah Sadar Din, and the first time the journalist Sanam Maher made the journey, her eyes widened at every turn. In Dera Ghazi Khan, a town close to the village, none of the faces of the women she saw on the streets were visible. Some wore what looked like black ski masks with slits for their eyes. Others were covered by burqas with no eye-slits at all and so extensive that she felt half naked under her own dupatta (scarf). A thin funnel rises from the top of this kind of burqa: a device to allow air inside so that the wearer does not suffocate. Her contact in the town, noticing her staring, mentioned a place not far away, where the tribal belt of Balochistan province starts: the women there, he told her, were not given shoes. She was confused. Why not? “You’ll never look at any man if you’re scared of where your naked foot might fall when you leave your home,” he replied impatiently, as if it was the most obvious thing in the world.

Maher, who is based in Karachi, was in Shah Sadar Din to investigate the life and death of Fouzia Azeem, AKA Qandeel Baloch, Pakistan’s first social media celebrity and the woman some like to describe as its Kim Kardashian. Baloch was born here, the daughter of a poor family, and when she was murdered on 15 July, 2016, her body was supposed to end up in the village’s brown river, a spot well known for being the final resting place of women who have died at the hands of their relatives in so-called “honour” killings. On the day in question, however, there were too many people around to manage this (another villager had died; crowds of mourners were gathering). Baloch’s mother found the body at home; her father informed the authorities. When the police arrived, Baloch was still lying where she had been drugged and asphyxiated, in a bedroom at the small house that she rented for her parents in Multan. She was just 26.

“Visiting Shah Sadar Din was a huge culture shock for me,” says Maher, whose book about the case, A Woman Like Her, is published in the UK next month (it has already caused something of a sensation in south Asia). “The women were so completely covered: I’d never seen that anywhere that I’d lived or worked. But it’s important to say straight off that, though this is typical of south Punjab, it has nothing at all to do with religion. These [dress codes] are cultural diktats, just as honour killing and other forms of violence against women are cultural diktats. This is men wanting to control how the women around them live.”

Maher had become interested in writing about Baloch because she felt that her life was a good, if rather extreme, example of the tensions that currently exist for the young in Pakistan; of the difference between where they find themselves in society, and where they would like to be. As she puts it: “My generation is connected to the world in ways that previous generations never were, and because of that we aspire to live and to behave and dress in certain ways. Yet we’re also rooted in a physical space that doesn’t necessarily allow for those aspirations.” But now, in Shah Sadar Din, she saw something else. “I was amazed by Baloch’s gumption. When I went to her village, it struck me almost for the first time just how big a deal it was for a woman to get out of that situation.

“I didn’t want to put her on a pedestal in my book; I want people to make up their own minds about her. But I remain amazed by her, and it is very cool to be getting messages from readers across Asia telling me that, though they’d begun by wondering why I wanted to write about someone they saw as trashy, they now have real compassion for her.”

Qandeel Baloch first came to public attention in 2013, when she auditioned for the reality singing show, Pakistan Idol. Though she wasn’t chosen by the judges, who mocked her high-pitched voice, her performance – and the tears she supposedly shed on being eliminated – soon went viral. Thanks to this, she began to pick up occasional media work: modelling jobs, appearances on chat shows, gigs plugging products on her Facebook page. But how to sustain people’s interest? As a young woman with few contacts, no money and not much obvious talent, her only option was to exploit social media, something at which she turned out to be highly adept. In 2015, for instance, a scrappy but rather pert 20-second video she made of herself known as How I’m Looking? resulted in her inclusion in Google’s list of the top 10 most searched for Pakistanis online.

There are more than 44 million users of social media in Pakistan, but the addicts among them are (this is the same the world over) easily bored. People scroll and scroll, and then move on. Baloch had no choice but to repeatedly up the ante if she wanted her followers to keep talking about her, and if this meant pushing against the boundaries of what was acceptable in Pakistan, it was a risk she was willing to take; opprobrium, after all, was just another form of fame. In October 2015, when Imran Khan, the former cricketer who is now Pakistan’s prime minister, announced the end of his second marriage, Baloch launched an online campaign to become wife number three (every TV channel screened her “press conference”). The following February, she released a message in which she denounced those conservatives in Pakistan who regarded the celebration of Valentine’s Day as un-Islamic. In March, she offered to perform a striptease for Shahid Afridi, the captain of the Pakistani national cricket team, if the side beat India in the World Twenty20 Cup. Finally, in April, she appeared on a comedy news show with a 50-year-old mullah, Mufti Abdul Qavi.

The cleric, something of a media star himself, did not rise to the bait offered by the show’s presenter, who asked him what he thought of her offer to Afridi (he also wondered aloud if striptease might not be a useful weapon in the national effort to deradicalise Islamic militants). But Qavi did say that he would like to meet Baloch again the next time he was in Karachi, where she was living by then. It isn’t clear, now, which of them made sure his seemingly throwaway request became a reality, but what we do know is that in June, Baloch released images of a meeting with the cleric that had taken place in a hotel room. In one, she poses in Qavi’s distinctive cap, her mouth open in a wide ‘O’ that suggests a certain disrespectful naughtiness on both their parts. In a short video, meanwhile, Qavi can be heard announcing that he intends, in the future, to offer her religious guidance.

In this moment, the die was cast for Baloch, for all that she would later insist that Qavi had behaved inappropriately towards her, and that he was “a blot” on the name of Islam. The encounter triggered a media storm, the main consequence of which was that the press was now determined to find out more about her. Things she had long kept hidden – not only her real name, and her humble background, but also the fact that she had run away from an arranged marriage to her cousin, seeking sanctuary in a refuge, and was now divorced and forbidden to see her son, Mishal – were soon revealed to a transfixed public. “Here was a woman who managed to fool everyone,” says Maher. “She had created a persona that we all completely bought into.” Meanwhile, back in her village, people began to torment the youngest of her six brothers, Waseem. They would come into the mobile phone shop that he owned and ask him, sniggering, if he could download his sister’s latest videos for them. In the public confession he made before the press following his arrest the day after his sister’s body was found, he gave as his motive “the way she was coming on Facebook”. A reporter wanted to know: was he ashamed? “No,” he said, sticking out his chin. “I have no shame.”

In her book, Maher traces Baloch’s journey from Shah Sadar Din to unlikely celebrity, uncovering new details of how she pulled off her transformation (for a time, for instance, she worked as a hostess for a Multan bus company, welcoming passengers on board and serving them cardboard containers of biryani). She talks to her parents, Muhammad and Anwar, who initially condemned their son, even calling for him to receive the death penalty, as well as to many others of those who knew her (in all, Maher did 125 interviews while she was researching the story). But she also looks at the wider effects of social media on Pakistani women. Increasingly, men are using it to shame women, and even to blackmail them, by threatening to release images, doctored or otherwise, online if they do not behave as they should. In this sense, the internet is for them just another control mechanism.

One story told by Maher sticks in the mind: that of Naila, a 22-year-old university student who killed herself in 2016. No one is certain, but it seems likely that she had discovered that a man she had been involved with had nude pictures of her.

“What shocks about Naila,” says Maher, “is that those who were supposedly there to protect her – her teachers – were saying things like: if young women want to be safe online, they shouldn’t send anything to anyone that they wouldn’t show their father or brother. Their attitude was: you’re asking for it. But let’s say that you’re in a relationship. You take a slightly suggestive picture, and send it to your boyfriend. Then the relationship fizzles out, and he threatens to send the picture to your family. Who do you go to? No one is sympathetic.”

Many women in the UK feel unsafe online. But as Maher points out, the stakes are vastly higher in Pakistan. “It can very quickly spiral from someone disliking an opinion you have to real violence. It’s really not just a case of words on a screen. This is an exciting time for us. Groups that were previously marginalised – queer groups, religious minorities – have found a space online. It is a moment of real freedom. But it comes with real danger. We’re starting to be smarter about online safety, but then, so are the people who don’t like our opinions.”

By the time Baloch was murdered, there had already been an estimated 326 so-called “honour” killings in Pakistan in 2016, of which 312 victims were women. Six days after her death, a parliamentary committee approved a bill that closed a legal loophole that had allowed relatives of the deceased to pardon perpetrators, or to receive “blood money” as compensation for the crime, enabling the killers to walk free. Since the change in the law, those found guilty will face a mandatory sentence of life imprisonment; relatives of the deceased can only now prevent the killer from receiving a death sentence.

Yet still the killings continue. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan estimates that at least 524 such murders occurred between October 2016, when the amendment came into effect, and October 2017.

“If things are really to change, we need a systemic shift in the education system,” says Maher. “Children need to be taught that this is not a religious thing, and that it can’t be excused on those grounds – and parents need to teach their sons that they have no more rights than their sisters.” Waseem Azeem remains in prison, but he has not been convicted of Baloch’s murder: “These cases can get dragged out for years. All we do know is that he can’t get off scot free.” Will his parents save him from the death penalty if a judge decides to impose it? Who knows. But as Maher points out, they now rely entirely on their sons financially – something that may, in the future, play a part in whatever they decide.

For Maher, working on this story wasn’t easy: “At one point, I said to my editor: every woman in this book is either dead or receiving death threats. It really started to weigh on me.” In Pakistan, many of the bigger book stores have been reluctant to stock A Woman Like Her; others keep it under the counter, as if, she says, “I’d written porn, or something”. But she also understands that she has privileges that her subject could only have dreamed of. “I think about this often,” she says. “I have opportunities that Qandeel didn’t. I have been able to talk to men who thought she deserved to die, and yet I was safe because of my role as a reporter. I got to leave, and go back to my own home. Sometimes, I struggle with this. No one ever asked her to write an op-ed in the New York Times, but [in death] she is getting me all this attention.”

What does she think Baloch’s legacy, if any, will be? Is it possible that the murder of this funny, smart yet rather naive young woman – one who began to talk, towards the end of her life, openly about feminism – will prove to be some kind of turning point in Pakistan?

“Well, we’re not done with her yet,” she says. “This happened in 2016, and three years on, we’re still talking about her. Women here take great courage from what she said and how she behaved. We tend to have these moments in Pakistan. They’re often, as was the case with Malala [Yousafzai, the Nobel laureate, who was shot on a school bus in Pakistan in 2012], brought on by great violence. They’re a moment of reckoning, when we hit pause and ask where we are going? It happened with Qandeel, too. When I see the pictures of women’s marches here, her face is always in the crowd: people wear masks of it. Her legacy is to encourage young men and women to think that if she could speak out, we should all at least try to do the same ourselves.”

Extract: A Woman Like Her by Sanam Maher

Fouzia Azeem, otherwise known as Qandeel Baloch, first came to the attention of the public three years before her murder, when she auditioned for Pakistan Idol, the reality singing show, in 2013.

Qandeel snaps her fingers and dances and sits on the hood of a car, bouncing her head to the music playing from her mobile phone. “I’m a professional model. I do modelling, shoots, brand shoots,” she explains in a video recorded earlier at what appears to be her home. Her cheeks have been rouged and her eyebrows are swiped with too much dark powder. Her hair, parted down the middle, is pinned on each side with a schoolgirl’s barrettes. “I love singing,” she says. “It’s not just a hobby, but a passion. I feel I can be Pakistan’s idol.”

“What’s your name? asks the actor judge when Qandeel walks into the room for her audition. “Pinky?”

“Qandeel Baloch.”

“Okay, I thought maybe it’s Pinky.” The judge points to her outfit. “Everything is pink.”

“You look so beautiful,” Qandeel gushes. “I always see you on TV, but mashallah, you look so beautiful.”

“Feel free to praise him too, or he’ll get offended,” the actor says, gesturing towards the male judge.

“Oh, there’s no point praising men; it makes no difference to them,” Qandeel replies.

Qandeel says she is nervous. She puts on a little girl’s whining voice, and the judges cajole her to give it her best shot. But when she finally does sing, she is a natural. She isn’t rooted to that oval plastic mat like other contestants. She walks forward, beckoning to the judges with her arms, beseeching them with her words, closing her eyes as she sways. She stares straight into the camera. She isn’t nervous; she is performing.

Later, the producers add some effects to the clip. One judge has smoke billowing out of her ears. When Qandeel hits a high note, there is a sound like a spring recoiling. The male judge buries his face in his hands.

When they tell her to leave, she strokes the hair falling from those two schoolgirl barrettes and gives a small smile, saying in that little girl’s voice: “Don’t reject me please.” She pouts. “I want to sing some more.”

The actor walks over to her and holds her by the shoulders and leads her out. The male judge pretends to cry.

“You fooled me,” Qandeel wails to the cameras waiting outside. “I told my parents I’m doing this audition and they’re so hopeful now. Now what am I going to say to them? They will just think: ‘They rejected our daughter.’”

She is on the verge of tears, her breath catching on each word.

“Don’t worry. Cheer up, okay?” the actor says, patting her shoulder. “We’ll see you doing modelling some day.” As she walks away, Qandeel covers her face with both her hands and lets out a wail. The show’s host pushes the mic towards her. She turns back to him, doubling over as she sobs. Her shrieks echo in the hall.

There is no one else there. The other contestants have gone away and it is now dark outside. The cameras follow her as she cups her face in her hands, the baby-pink painted nails covering her eyes as she cries all the way out of the door.

“Poor Qandeel has wept off all her cajole [kohl],” the voiceover to the clip would later remark.

Liars.

All frauds.

Watch it again. Do you see any tears?

What I did there was my acting. Everything was planned from the start. It’s all bakwaas [fake].

The audition clip went viral. To date, Qandeel’s five minutes on Pakistan Idol have racked up well over 10m hits on YouTube.

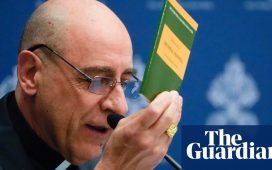

• A Woman Like Her: The Short Life of Qandeel Baloch is published by Bloomsbury on 11 July (£16.99). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £15, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99