AKRON, Ohio — Vinny Mercurio’s miraculous tale of survival is now measured in more modest but no less important steps.

After suffering a hemorrhagic stroke on Nov. 12, 2017, the now-13-year-old eighth grader once had his progress marked by major milestones.

Twenty-six days in Cleveland Clinic’s Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, 26 more on the hematology floor, 77 at the clinic’s Children’s Rehabilitation Center. Ten weeks of outpatient rehab.

March 6, 2018 — the day he came out of his minimally conscious state and began talking again.

Now Mercurio pushes forward with smaller goals and rewards — popcorn at the Winking Lizard, money for video games, a Fitbit.

Recording his first birdie in golf doesn’t serve as the same kind of motivation, although it’s a desirable thrill he nearly experienced earlier this month.

Mercurio participates in a program on the campus of the Wharton Center at North Olmsted Golf Club provided by The Turn, which has served Northeast Ohioans with physical disabilities since 2002. Mercurio uses an Ottobock paramobile to play on The Turn’s PGA Junior League team with his brother Tony, 11. The device was purchased with a donation from Northern Ohio Golf Charities through funds raised at Akron’s PGA and Champions Tour events.

On Wednesday morning ahead of Thursday’s first round of the Bridgestone Senior Players Championship at Firestone Country Club, Vinny and Tony Mercurio will be part of one of eight 10-person teams in the Firestone Junior Cup on the Fazio Course.

The winner will be decided by a two-hole shootout between the top two teams, but the outcome likely won’t change Vinny’s feelings about participating. When it was suggested he might meet some famous golfers that day, Vinny couldn’t resist a quip that figuratively patted himself on the back.

“I already know a good golfer,” he said.

PGA Junior League provides competitive outlet

The sport has been a godsend for Mercurio, an outlet for the competitiveness he used to channel into basketball, baseball and flag football.

“It’s cool being outside and with my friends and teammates and golfing with my brother and being a little competitive, but having fun,” Mercurio said of The Turn program in a June 9 interview at Firestone.

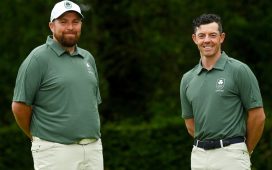

Tony Mercurio, 11, and his brother Vinny Mercurio, 13, at the Firestone Country Club in Akron, Ohio. Photo by Karen Schiely/Beacon Journal

He practices at The Turn on Mondays and Wednesdays and usually plays six holes on Saturdays or Sundays. Erin Craig, an assistant golf professional in her third year at The Turn, pointed out Mercurio was just a few days removed from lipping out for birdie in his weekend game.

“I like golf,” Mercurio said. “The doctors didn’t even think I would get out of bed.”

The Firestone Junior Cup will be another chance for parents Chuck and Betty Mercurio to marvel at how far Vinny has come since that unforgettable day 3½ years ago when he complained of a headache.

‘What is happening?’

The boys were watching the Cleveland Browns game against the Detroit Lions with their dad, but lost interest and decided to play basketball in the driveway. When they came in, Vinny said his head hurt. Chuck Mercurio said the pain became progressively worse and Vinny started to cry.

Betty Mercurio drove Vinny to the emergency room. Vinny lost consciousness in the car and Betty said she began yelling at him.

“By the time they got him into a CAT scan, his heart had stopped,” Chuck Mercurio, a middle school math teacher, said during the interview at Firestone. “By the time I got there he was intubated.

“You walk in and you see tubes down your kid’s throat, it’s like, ‘What is happening?’ It was completely out of nowhere.”

Vinny had a blood clot that caused a stroke near his brain stem, which controls the heart, consciousness, breathing and balance, and the prognosis was dire.

“We were told he wouldn’t make it or if he did, he’d be a vegetable for the rest of his life,” said Betty Mercurio, a manager at the Cleveland Clinic. “He is truly a miracle. … the fact that he can do everything that he can today and how much he continues to progress.”

Chuck Mercurio said multiple neurologists have been amazed when they see Vinny, then look at his chart and past test results. After Vinny regained consciousness, he was in a wheelchair, in diapers, on a feeding tube. Now he attends school and hopes to eventually shed his walker.

“They say, ‘I’ve never seen this information and a child that can do all that,’” Chuck Mercurio said. “He has not lost any cognitive functioning, which no one can explain. I remember a neurologist coming in, they brought in a brain scan and showed us these darkened areas in his brain and he was explaining, ‘This is irreparable. There’s going to be a lot of loss of all kinds of stuff.’ That was devastating.

“They just did an MRI a couple weeks ago. … They want to try to find out why and [if] anything like that going to happen again. But everything looks good and they don’t see any evidence. They still don’t know; they’re not going to know. Everybody has their theories of what happened, but it’s just going to be a mystery, unfortunately.”

The Mercurios told Vinny he was asleep for three months. He remembers nothing from that time, but recalls everything before the stroke save for Nov. 11. When he started talking again, Vinny began setting a goal each month for motivation.

“If he could get off pureed food, he wanted to go back to Winking Lizard and have their popcorn,” Betty Mercurio said in a June 10 phone interview. “If he could get off his leg injections because he wasn’t moving around enough, he wanted a Fitbit because then he could be in his walker all the time using the Fitbit. That’s how we’ve kept him motivated, allowing him to pick whatever reward or incentive he wants. Sometimes they get a little more expensive than others, but it keeps him going. Nowadays it’s more like video game money.

“He doesn’t have limitations for himself. Kids are jumping in the pool or jumping off the porch and he’ll say, ‘I want to do that.’ Our hearts break because we’ll say, ‘He can’t do that,’ but I’m like, ‘Let’s find a way you can do that.’ I think that’s what’s kept him going — he wants to keep getting better, he wants to keep up with his friends. He’ll tell you he wants to be normal again. I think because he’s got that mindset that he’s going to keep fighting and getting better. That’s the drive that keeps him moving forward.”

Vinny Mercurio, 13, hits balls on the driving range at the Firestone Country Club in Akron, Ohio. Photo by Karen Schiely/Akron Beacon Journal

The Turn golf program was a suggestion of Nate Ogonek, Vinny’s physical therapist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s Hospital. Betty Mercurio believes that has played a “huge” part in Vinny’s improvement because before Vinny’s stroke both boys were playing sports every week.

“When our physical therapist Nate referred us, it was like, ‘Wow, he could do a sport?’ You saw that light in his eyes again, that’s what he loved,” Betty Mercurio said. “He’s proud to tell people he plays a sport. To him it’s not adaptive golf — he plays golf.

“This past year he got to play golf on a team with a bunch of other kids. I could see it just gave him that confidence, that competitive edge. Him and his brother played baseball together, so the fact they could play a sport together again, we love [it]. We’ve done it as a family. It’s just opened up a new world.

“Once we learned about golf, it was like, ‘What else is out there?’ The achievement center has adaptive football and baseball, we added that, and he’s loved that. It gives him back that social opportunity, just his opportunity to be a kid again.”

The Turn’s instructor Craig hopes to get Vinny into a solo rider, a cheaper and more available kind of golf cart with a swivel seat that doesn’t raise as high to help a player stand. The Turn staffers tried it with him last year and his legs were not strong enough, but Craig believes that will happen by the end of this golf season.

Using the solo rider would allow Vinny to play more courses, Craig said.

“He’s definitely gaining strength in his legs,” Craig said during the interview at Firestone. “Our first summer I had with him we were just doing junior camps and our goal was just to hit the ball. Now our goal is to hit the ball far. It’s really neat to see how far he’s come. I get chills just talking about it.”

Craig said the PGA Junior League team program at The Turn has kids ranging in age from 7 to 15. Some are as old as 95, and she said many have remarked that if they knew such paramobile devices were available they would have taken up golf sooner.

“As Vinny likes to say, it makes him feel normal,” Craig said.

Vinny said he doesn’t set goals for golf like he does in other phases of his rehab, adding, “but when I hit a really good one, I’m really excited about it.”

When his recent near-birdie was mentioned, his mother wouldn’t rule out Vinny making that accomplishment more of a priority.

“That’s right,” Betty Mercurio said with a laugh. “He’ll keep striving.”