But by the end of the first act, End of the Century establishes itself as something more than a romantic melodrama — because, as it turns out, Ocho and Javi aren’t strangers at all. Apparently, they shared an intimate tryst before, almost 20 years ago. As the two sit on a roof several hours after their hookup, drinking wine and eating cheese, Ocho casually admits, “You know, I have a weird sensation — I feel that we’ve met before.” Then, without waiting a beat, Javi confirms these suspicions. “We have met before,” he replies matter-of-factly.

Almost immediately, we’re transported to a new timeline. Again, Ocho is getting off a train. But now, he and Javi are both in relationships with women. The switch is initially jarring — at least until you realize you’ve jumped backward in time — and the rest of the film plays out in similarly trippy detail. As the men begin to parse out their pasts and figure out how it has impacted their presents (and possibly their futures), the film jumps between alternate timelines — some real and some, we have to assume, imagined — morphing End of the Century into a story that is less concerned with how relationships form over a small amount of time, and more with how they can significantly evolve over long periods.

And the film’s fascination with the passage of time doesn’t stop there. Though Javi presently works as the director for a popular Spanish-speaking kids show in Berlin, he was once an aspiring filmmaker, working on a documentary about the dawning of the new millennium (hence the film’s title). According to him, nothing will really change in Y2K, even though everyone around him is anticipating some drastic new beginning. The film keeps the younger Javi almost trapped in time, as he debates whether finishing it is even a possibility. He explains to Ocho in the flashback that he needs to wait until after the turn of the century to prove his point, but also worries that his idea won’t even be relevant after we’ve passed that pivotal moment.

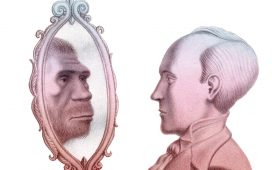

Javi’s perspective becomes more interesting as the film goes on — particularly when juxtaposed with their current lives. In the past, when they first meet, the two share a conversation about how they hope their futures will play out. Mentioning his experience growing up as an only child, Ocho speaks excitedly about eventually wanting lots of kids, while Javi, referencing his own childhood in a “very chaotic” household, shoots down any possibility. Yet in the present, it’s Javi who has settled down and is now married with a daughter he loves more than anything. Ocho, on the other hand, talks of leaving his boyfriend of 20 years because “he missed being alone” and craved “complete freedom.” What a difference twenty years can make, the film seems to suggest — though never cliché. It begs the question of when we can truly “know” ourselves and be honest about our desires while also exploring the ways our life trajectories can have a profound impact on our worldviews as time goes on.