In the 73 years since her death, the artist and printmaker Tirzah Garwood (1908-51) has mostly been “Mrs Eric Ravilious”. Now, a decade after Dulwich Picture Gallery’s acclaimed Ravilious survey, Garwood takes the spotlight in an exhibition that reveals for the first time the full extent of her talent and output.

The curator James Russell first saw Garwood’s work 20 years ago while researching the exhibition that would restore Ravilious to public consciousness. Ever since, Russell says, he has “been looking for an opportunity to put on a show; the problem is that she’s so obscure. Even for an overlooked artist, she’s incredibly overlooked.”

Garwood’s moment arrived with the 2012 publication of her vivid, witty autobiography Long Live Great Bardfield, followed in 2022 by the word-of-mouth hit film Eric Ravilious: Drawn to War. For Dulwich, which has consistently championed women artists from Berthe Morisot to Winifred Knights, the exhibition is a natural step, following on from its 2018 show Edward Bawden, dedicated to Garwood and Ravilious’s great friend with whom they lived at Great Bardfield in Essex, between 1932 and 1934.

A ‘clear, precise and witty’ style

Though successful before the age of 20, Garwood is mainly recognised for the assistance she gave Ravilious in the early years of their marriage, when she would cut away the backgrounds of his wood engravings. While she was able to assimilate his style when necessary, Garwood’s own distinctive, unconventional hand, Russell says, is “clear, precise and witty”. The show will feature more than 80 of her rarely seen works, from oil paintings to engravings, sketches, collages, textiles and patterned papers.

Garwood met Ravilious at Eastbourne School of Art where he instructed her in the booming medium of wood engraving. But her collection of Victorian books was her formative influence, reflected in early wood engravings that reveal her love of natural history and flair for satire. This culminated in Relations, a series of humorous vignettes of everyday life, commissioned in 1930 by Curwen Press, but never published. Though Ravilious was supportive of Garwood’s work, the pressures of marriage and domestic life diverted her talents to quiltmaking and needlework in which she sometimes reprised earlier prints.

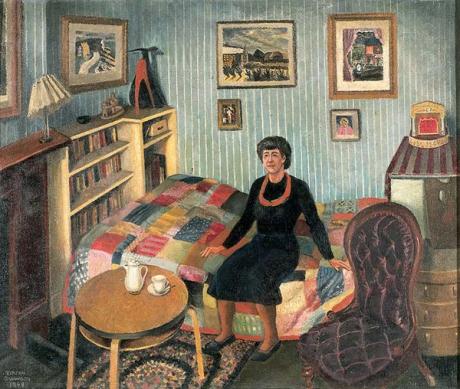

A move to Castle Hedingham in Essex in 1935 was a turning point, and Garwood established herself as one of the best marblers in the country, selling decorative papers to London’s design shops, and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Diary excerpts from 1941 reveal a terrific work rate, with paper orders jostling with jam-making, the care of a baby and two others under seven. Ravilious’s death followed hard on Garwood’s breast cancer diagnosis in 1942; from that point on, Russell says, her work “goes off immediately with a bang”, as she switched to oil paints, creating strange, unsettling scenes that combine a rustic Victorian style with a childlike eye, and sometimes a knowing dialogue with Ravilious. The Surrealist sensibility gained strength in the final year of her life, her ghostly self-portrait, Spanish Lady (1950), reminiscent of Leonora Carrington’s work.

For Russell, these final works have special force. “Was she an important artist? To me, in her terrible situation when she knew she was going to be leaving her children [in death], she found a language to talk about it that was unlike anyone else’s. I think that’s an extraordinary achievement.”

• Tirzah Garwood: Beyond Ravilious, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, 19 November-26 May 2025