It sure didn’t feel like January in the Northeast over the past few days. At the time of year when the days are near their shortest and the weather should be near its coldest, temperatures across the region warmed to the high 60s and low 70s — 30 to 35 degrees above average. Records for daily highs were broken from Columbus, Ohio, and Pittsburgh to New York City and Bangor, Maine. Many residents took the warm spell as a belated holiday gift and went outside to cycle or jog or picnic with friends and family as if it were spring.

Some of the readings were especially eye-popping: Highs of 70 were seen in Boston on consecutive January days for the first time since record-keeping began in 1872. Buffalo, where the temperature on the same date last year never went above 20, reached 67 on Saturday. Charleston, W.Va., hit 80 degrees. It couldn’t last, of course: A cold front moving in late Sunday was expected to reset the region’s weather much closer to the seasonal range. But what was that anomalous warm spell all about? Here’s what the experts say.

Was it the fabled ‘January thaw’?

January is when the annual weather cycle reaches bottom in North America, with the coldest average temperatures expected around Jan. 23 — about a month after the shortest day of the year, the winter solstice. But people have long noticed and remarked on the tendency, especially in the Midwest and the Northeast, to have brief warm spells around that time, an event popularly known as a January thaw.

Climatologists call the January thaw phenomenon a “singularity,” a noticeable diversion from the usual seasonal weather that tends to recur around the same calendar date. “Indian summer” — a warm spell in the late fall, after the first frost — is another example.

January thaws happen often, but not every winter, and they rarely bring truly bizarre weather. A typical one features high temperatures that are 10 to 20 degrees above normal — in most of the Northeast, enough to make the difference between freezing and thawing.

Was this warm spell a January thaw?

Technically, no. In order to thaw, you have to have frozen in the first place, said Jay Engle, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in New York. And the Northeast has not been frozen — the weather in the region has been on the mild side since mid-December, he said, so the recent record-breaking days were just a change from warm to warmer.

It also came a bit early; January thaws are most common in the last third of the month.

According to the Farmer’s Almanac, a January thaw doesn’t have to melt away ice and snow to qualify. In areas that experience the harshest winters, the phenomenon may only moderate the cold and attract little notice. And for areas where milder winters are the norm, a January warm spell might be better described as a “false spring.”

So what was to blame?

The warmth was blown into the Northeast by the jet stream, the powerful atmospheric current that drives weather patterns across the continent. In the winter it usually allows cold air masses to descend from Canada, but lately it has been pushing very warm air northeastward from the Gulf of Mexico.

“This is an impressive, couple-day stretch here,” Mr. Engle said, noting that the records that were broken over the weekend were in many cases 40 years old or more.

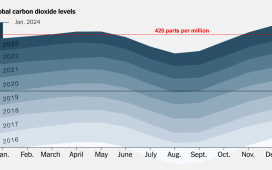

Before anybody says “global warming,” though, a reminder about the difference between the climate and the weather. The world is clearly getting hotter overall, experts say, making some kinds of weather events more frequent and more severe. But there is no direct link between those long-term global trends and the short-term fluctuations we experience in the weather from day to day and season to season — not the record warmth of the past few days, and not the next arctic cold snap to sweep through, either, whenever it may come.