It is “smog season” in Lahore. Along with cities in the plains of the Punjab province, October is now popularly called the fifth season in Pakistan as the burning of stubble in the fields after the rice harvest takes the already poor air quality to record lows.

On Monday, Lahore took the world lead on several measures of poor air quality. According to Swiss-based IQAir, which partners with the UN and other agencies to measure pollution, the air quality index was 299 – just two points short of hazardous, followed by Delhi scoring 207. An AQI of 151 to 200 is classified as “unhealthy”, 201 to 300 “very unhealthy” and more than 300 as “hazardous”.

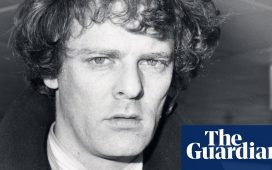

Yet when British artist Dryden Goodwin was looking for an activist fighting for clean air in the city to draw as part of a showcase for this month’s 2024 Lahore Biennale 03, he struggled to find a volunteer.

Reluctantly, the founder of the Pakistan Air Quality Initiative, Abid Omar, agreed to sit for the project himself, leading to more than 230 pencil sketches of Pakistan’s leading clean air campaigner now being on display across the smog-choked city.

Omar says: “I was asked to find an air pollution campaigner in Lahore, but the topic is often overlooked, and we couldn’t find anyone.”

So he agreed to sit for Goodwin himself and is now pleased with the results.

“Breathe: Lahore is a powerful reminder of the urgent need for clean air,” Omar says. “I hope there will come a day when there will be no shortage of candidates campaigning for clean air in Pakistan.”

Ranging from torso studies to detailed body parts, the drawings have been transformed into more than 1,500 posters, digital billboards, and projections across Lahore. Goodwin aims to spark urgent discussions about environmental challenges and, along with the pictures of Omar, there are sketches he made of six British activists.

Produced by the UK organisation Invisible Dust, which connects artists and scientists to create powerful art that fosters emotional connections to urgent environmental issues, Goodwin’s Breathe: Lahore marks the international debut of his project.

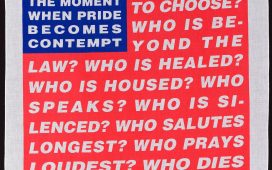

The screens across the city vary in size, with most measuring 2 metres by 1 metre (6 feet by 3 feet) and some as large as 12 metres by 6 metres. Goodwin created a series of eight digital animated posters, each featuring a clean air activist’s words, along with a triptych for the larger screens.

The pièce de résistance is an installation at Lahore’s historic Bradlaugh Hall, showcasing the completed animation comprised of 1,617 drawings. “This contemplative space, set away from the busy road, features a 41-minute and 3-second animation,” says Goodwin. The animation varies in rhythm; at times it slows down, while at others, it maintains a regular pace, capturing the tension between stillness and movement as each activist “fights for breath”.

Through hundreds of intricate monochrome pencil drawings Goodwin captures people moving through laboured breathing. He explains he wanted to “induce a heightened consciousness about the act of breathing”.

Weather experts had warned that Lahore, bordering India and home to nearly 15 million people, would experience extraordinary poor air quality two weeks earlier than last year.

Smog is characterised by a high concentration of particulate matter. The smallest such particles, measuring 2.5 thousandths of a millimetre in diameter or less, are the most dangerous, as they can cause irreversible damage when they infiltrate the lung lining.

Goodwin first became interested in air pollution in 2012 when he made an animation of more than 1,300 drawings of his then five-year-old son.

after newsletter promotion

“The motivation was to express my son’s vulnerability but also a universal fragility when growing up breathing toxic air,” he says, adding that it was through conversations with Prof Frank Kelly, an expert in lung health at Imperial College London, that he became aware of how adversely children are affected.

In 2022, Goodwin launched Breathe:2022, followed by Breathe For Ella in 2023, honouring British nine-year-old Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah, who died in London in 2013 and became the first person globally to have air pollution listed as a cause of death.

For Breathe For Ella, Goodwin created over 1,300 sketches of six local clean air activists from his home borough of Lewisham, including Ella’s mother, Rosamund Adoo-Kissi-Debrah CBE, who continues to advocate for “Ella’s Law” to enshrine the right to clean air in UK law.

Goodwin says he was always questioning the paradox that air – “sustains but corrupts our body too” and yet is often taken for granted.

For Omar, who has been campaigning around air pollution since 2016, it was a valuable experience.

“I began to view the air we breathe in and out with a newfound respect, after sitting for Dryden,” he says. “The experience of gasping for air, feeling the weight of each breath, made me acutely aware of our vulnerability to air quality.”

He described the four-hour sessions where he had to be constantly “out of breath” while Goodwin drew remotely from London. To help capture his laboured breathing and postures, Omar would go for a run or use an exercise bike.

Lucy Wood, producer of the Breathe series from Invisible Dust, says that the team hopes to take the project to other cities.

“The idea is to have a growing collective of individuals with each new city, striving for clean air,” she says. Her eyes are set on Delhi, home to the second worst air quality in the world, as a next stop in the global tour of Breathe and to connect with local partners in each place, growing momentum and learning with each destination.

Scientists say improving air quality in Pakistan will be futile unless India and the rest of South Asia – also acts.

This year, the Conciliation Resources’ South Asia Programme has been working to bring together environmental experts from India and Pakistan to address the challenges. It held a meeting earlier this month in Nairobi for former ambassadors, parliamentarians, and military personnel from both countries to engage with experts. They collectively recognised that emphasising air pollution as a serious issue could serve as an effective “confidence-building measure” to pave the way for renewed bilateral dialogue.

This dialogue is crucial between the nuclear-armed neighbours, whose relations stalled in 2019, when India revoked the special status of Jammu and Kashmir, accusing Pakistan of supporting a longstanding armed insurgency in the region.