Before the initial release of “Howl’s Moving Castle” 20 years ago, Akihiko Yamashita spent nearly two years working as the supervising animator on the Studio Ghibli film.

“I really have no idea how many pages of drawings there were or how many cels we drew. I just know that we worked a huge amount and we drew a huge amount,” Yamashita tells Variety through an interpreter. “Nowadays, we talk about work-life balance, but in those days, there was no concept of that.”

Yamashita first worked with animation maestro Hayao Miyazaki as a key animator on 2001’s “Spirited Away.” Over the past 20-plus years, he has served various roles on Studio Ghibli films, including as an assistant supervising animator on “Ponyo” (2008) and a key animator on “The Wind Rises” (2013) and “The Boy and the Heron” (2023).

Yamashita recalls working 14 hours a day on “Howl’s Moving Castle” during the last six months of production, noting that there were “no Sundays” nor “time off during the week.” However, after Miyazaki’s film was complete, the supervising animator received three months of paid leave.

“I realized that I could only do this because I was in my 30s in those days,” Yamashita says. “I wouldn’t be able to do that now at all.”

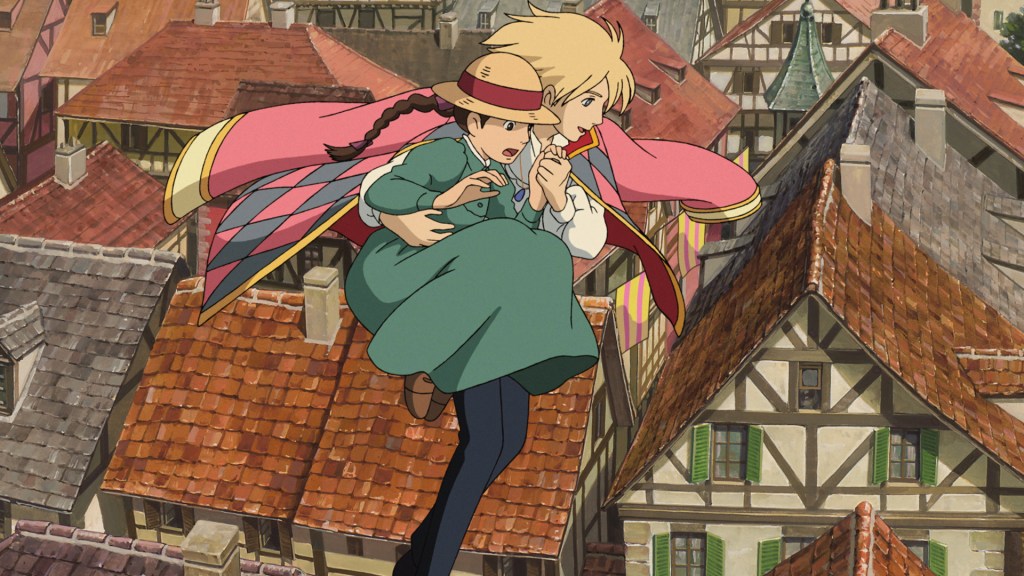

Based on Dianna Wynne Jones’ 1986 fantasy novel of the same name, “Howl’s Moving Castle” follows a young milliner named Sophie, who is magically transformed into a 90-year-old woman by the Witch of the Waste. On a quest to break the curse, the elderly Sophie takes refuge in a moving castle owned by a charismatic wizard named Howl.

In celebration of the 20th anniversary of “Howl’s Moving Castle,” now playing in theaters until Oct. 3 as part of Ghibli Fest, Yamashita spoke with Variety via an interpreter about his relationship with Miyazaki and bringing the animated fantasy film to life.

How does the animation process for a Hayao Miyazaki film differ from other animated projects you’ve worked on?

First of all, he is somebody who actually draws himself. From the layout to the storyboards — everything — he draws it himself. And let’s say a key animator has drawn some animation. If he doesn’t like it, then he will change it and draw a rough drawing. Then, the key animators and other animators have to bring that to the final stage.

Another is the way he thinks about animation. Other animation directors use animation to tell a story, but he tells the story through the animation. It’s all built into his storytelling.

What was the character design process like for this film?

In terms of Miyazaki’s method of working, he has rough sketches of — this isn’t necessarily used in the animation — but it’s his overall image of what he thinks the story and the film should be. This includes the images of the characters, the costumes, the facial expressions, the hair. For example, Howl being a blonde man — those kinds of images he draws, and then the animators need to figure out how to animate those kinds of images. In terms of animating the characters, I draw many pages, like 20 pages for a character, and how that character should be expressed. For this one, we had a little time, so I spent a month or so drawing and getting my hand used to the kinds of character drawings that would be required for animating the film.

Howl’s castle has such an intricate and detailed design. Could you describe the castle’s animation process? How many people were involved?

I’m not sure I can count. There were many, many people who worked on it. In terms of drawing such a large item like that castle, there would usually be a base design for it, and then various animators could draw from that base design. But in this case, there was no such initial base design. So there might be one scene where it was drawn one way and then another scene where the little house wasn’t in the same place. But somehow, even with these angle changes that may show different things, it looked like one castle in the end.

There may be different things stuck onto the castle, but as long as there’s the mouth and the eyes and the chimneys, then people just perceive it as the same thing. So, we take advantage of that sort of misconception on the part of the audience to draw slightly different things.

The music in “Howl’s Moving Castle” is one of the most beloved scores in film history. What was the collaborative process like between Hayao Miyazaki and composer Joe Hisaishi for the score? And were you involved in any way?

Those of us who are working on the animation don’t touch the music at all. That all happens at a higher level, at the top level, between Mr. Miyazaki and Mr. Hisaishi. We heard some of the demo-type pieces in terms of the image that was desired during our production work, but I didn’t hear the complete score until the film was finished. At that point, I was probably an audience member as well.

How did you feel watching the film for the first time with the music?

With the music, the impression of what a film is about can change drastically. Of course, I knew the story and the actual drawings and animation, but until the music comes in, it’s hard to tell the depth of the story. And the result can be good or bad, depending on how the music fits into the film. In this case, I think it was wonderful because “Merry-Go-Round of Life” was the theme of this film. It gave a real depth to the story and the animation.

What was your favorite scene to animate? And was there was a particular scene that was difficult to work on?

Of course, the whole thing was rather difficult. It took a lot of work, but it was also very interesting and fun. The one scene that I feel really worked well was one that showed how Howl was kind of a sexy character. And it’s the scene where, after Sophie enters the castle, and the next morning, Howl returns and comes right up to Sophie — very close to her — and says, “Who are you?” At that point, I had drawn a rough sketch with the movement, and I showed it to Mr. Miyazaki. There should have been more development and growth to that scene, but he said, “No, this is fine. This is good,” and, “We can move on to the next scene.” So that’s a scene where Howl is in profile, and I thought that worked really well, and I was very glad that it worked out well. It showed a different aspect of Howl — that he was a very attractive, sexy person.

What about your favorite character to animate?

Probably Howl because he is a handsome man and very attractive, but in terms of his inner self, he’s not that attractive. There are many people who are really good at their work and at their job, and they outwardly present a really fantastic image. But when they get home, they’re just slobs and sloppy, and they’re not really somebody you would look up to. So, that kind of duality interests me. The Witch of the Waste is also like that — she has this two-sidedness that also attracts me.

©Buena Vista Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection

What is your relationship like with Mr. Miyazaki? Has it changed over the years?

I have only a workplace relationship with Mr. Miyazaki. Actually, Mr. Miyazaki is my mother’s age, so I don’t necessarily have a master and apprentice relationship or a boss and underling kind of relationship, but it is a workplace relationship. And I think it’s hard to get close to Mr. Miyazaki.

But in terms of the casual conversations that we have within the workplace, we talk a lot about really local, inconsequential kinds of things. I used to live rather close to where Mr. Miyazaki lives, and I would sometimes run into Mr. Miyazaki and his wife on their walks in the neighborhood.

You’ve worked on many of Miyazaki’s films over the years, including “The Boy and the Heron,” which he said is his final film. Do you believe that’s true?

In terms of feature films, I think that probably is his last film. But he has directed eight short films that are shown at the Ghibli Museum. The museum has shown ten films so far, and I’ve made one film [“A Sumo Wrestler’s Tail”]. I would like him to make two more films to make it 12, and then I would have some work to do as well.

Why 12?

At the Ghibli Museum, one film is shown for a month. So if there were 12 films, then they would be able to work out the year with the 12 films.

This conversation has been edited and condensed.