While researching this book, Henry Mance worked briefly in an abattoir, or “a disassembly line”, as he aptly terms it. As he watched sheep being stunned, their throats slit and then hung up, still twitching, from metal hooks on a motorised track, Mance asked himself: “How did humans come to this?”

His book is an attempt to answer that question, as well as an exploration of how our attitudes to pets, livestock and wild animals have changed through history: “I wanted to know whether my love for animals was reflected in how I behaved, or whether – like my love for arthouse films – it was mainly theoretical.”

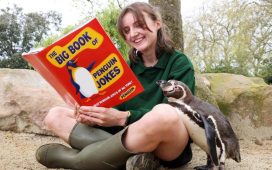

To understand the popularity of zoos, he talked to Damian Aspinall, owner of two safari parks. Every year in the UK and Ireland, 32 million people visit zoos and yet, Mance says, “we’re polluting our children’s minds” with this display of imprisoned wildlife. Mance visited Corgi Con in San Francisco (“people dressed as Corgis, and Corgis dressed as people”) to gain insight into our love of pets. Apparently, Americans spend $95bn a year on their animal companions, which is double their overseas aid budget. Mance also took a job at a pig breeding station, where he collected “overlays”, piglets suffocated by their mothers: “The piglets are roughly the size of human babies, with a similar skin tone and warmth”.

Mance argues that our relationship with animals is fraught with contradictions and governed wholly by “tradition and inertia”. We are quite happy to accept that some 1.5 billion pigs – mentally and socially complex creatures – will be killed this year around the world, but regard it as an outrage to slaughter a dog.

Indeed, in this era of climate emergency and zoonotic diseases such as Covid-19, when a quarter of mammals face extinction and an area of rainforest the size of a football pitch disappears every six seconds, it is our insatiable taste for meat and for dairy products that Mance identifies as the key problem with our relationship with animals. It could even prove fatal – for us and for every other animal. His conclusion is that our taste for meat and for dairy will cost us the planet: “We are the smartest species on earth; why do we insist on being the dumbest, too?”

He began the book as a vegetarian and is now, as a result of his research, a vegan – despite his wife (a vegetarian) warning him: “It’s divorceable.” But for Mance, “the mass-scale, thoughtless nature” of livestock farming is ethically and environmentally unacceptable: “If you really love animals, you can’t accept modern farming.” In the UK we slaughter 11 million pigs and 1 billion chickens a year: “When we say meat is cheap, what we really mean is that life is cheap.”

Meat eating is falling in countries like Germany but “surging” in Asia and Africa. Until the 1870s, Japan did not eat much meat but its diet changed with westernisation, as has India’s. Consumption of meat and milk is predicted to grow faster in the next three decades than in the past five. By 2035 global demand for meat will be 400m metric tonnes: “more than the weight of all humans on earth”.

Mance doesn’t believe that it’s always wrong to kill animals: he agrees with using animal tissues to save human lives, and thinks hunting wild animals (although not game shooting) can be justified for conservation reasons: “The hatred of hunting is outdated … give me a driven hunt over an abattoir any day.”

Although last year, 400,000 signed up to Veganuary, Mance is realistic: just 2% of British adults were vegetarians and 1% vegans in 2016. But Mance also shows that meat eating is shaped by culture, as children start eating it before they are old enough to question the practice. For this reason he argues that vegan meals should be served in schools and public buildings: “Hunting whales seems repugnant to most westerners because we know it’s possible to live without it. We don’t need whale oil and meat. Now we don’t need cow’s milk and leather either.”

Written with humour and humanity, Mance’s argument is both convincing and urgent: we need to make dramatic changes to our lifestyle if we want to prevent ecological catastrophe. By cutting out meat and dairy we may also open up a new and more respectful relationship with our fellow creatures: “The less we rely on animals for food, clothing and other products, the more we will be able to appreciate their needs.”