On Monday afternoon, Boris Johnson, the British Prime Minister, announced a new approach to help the country withstand a steepening second wave of coronavirus infections. Coming into force on Wednesday, England’s three hundred and forty-three local authorities will be split into three tiers—“medium,” “high,” or “very high” risk—which will carry their own restrictions on household mixing, gyms, pub curfews, and all the rest of it. The new strategy has been talked about in the media for weeks. At first, it was known as a “traffic-light system,” until people pointed out that there was no green, or low-risk, option. On Monday night, as the new rules were spelled out, it was clear that there wasn’t a red light, either.

Liverpool, which in early October had an infection rate of nine hundred and twenty-eight cases per hundred thousand people, will become England’s first “Tier 3” city, but its schools, shops, and restaurants will remain open. Socializing with people from another household will be banned, but pubs that offer a “substantial meal” will be able to serve drinks until 10 P.M. The government’s new rules were bruisingly negotiated with mayors and council leaders in recent days, because of the economic damage they will cause, but that didn’t stop widespread criticism of the measures when they were announced. “I am disappointed that the government has pressed ahead with this,” Andy Street, the Conservative mayor of the West Midlands, which includes Birmingham and Coventry (Tier 2 and Tier 1), said. Street argued that the restrictions on businesses will not affect the local epidemiology of the virus, which is spreading mainly in people’s homes, but that they will wreck the region’s hospitality sector. Scientists and public-health experts pointed out that the new system is not stringent enough to slow a national second wave of coronavirus infections and deaths.

Six months into the pandemic, the British government’s handling of COVID-19 is not dissimilar to what it was in the spring. A lot has happened, to be sure. At least fifty-seven thousand three hundred and forty-seven people have died of the disease; the economy has cratered. But the over-all strategy for dealing with the virus remains late, oddly complicated, and undermined by a dull, nagging incompetence. An hour after Johnson finished a televised address alongside Britain’s chief medical officer, Chris Whitty, to explain the virtues of the new tiered system, officials quietly released minutes from the country’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies, a panel of independent scientists that has been guiding the government throughout the crisis. The minutes showed that the critical moment to prevent Britain’s second wave has probably already passed.

On September 21st, twenty-seven SAGE experts, along with officials from Downing Street, reported on Zoom that the country’s infection rate was probably doubling every seven days and recommended a range of immediate measures to halt the spread. “Not acting now to reduce cases will result in a very large epidemic with catastrophic consequences,” the meeting concluded. The SAGE experts proposed a two-week national lockdown, known as a “circuit breaker,” to interrupt transmission, along with four other severe steps, including the closure of all bars and restaurants. Johnson and his ministers chose only one of the proposed measures, advising that people, when possible, should work from home. In the three weeks between the SAGE meeting and yesterday’s announcement, coronavirus cases quadrupled. Hospitalizations are at a higher level than they were in March. Temporary “Nightingale” hospitals, to cope with an overflow of patients, are being prepared in Manchester, Harrogate, and Sunderland. Whitty, who is diffident and not a good communicator, was asked Monday night whether he thought the Tier 3 restrictions, taken on their own, would be enough to slow the epidemic. “I am not confident—and nor is anybody confident,” he replied.

Adopting a local response to Britain’s second wave is smart politics. Mayors and council leaders will now, in theory, share some of the blame for Draconian decisions that have previously been imposed by officials in London. The approach also reflects reality. In the United Kingdom, health is a devolved responsibility; the governments of Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland have all been following slightly different policies since the start of the crisis. Johnson and his ministers have never had total authority over the handling of the epidemic, even if they were capable of exerting it. One of the reasons for the current political unease is the imbalance between the high infection rates in the towns and cities in the North of England—which have already been subject to restrictions for weeks—and the relative abeyance of the virus in London and the more prosperous South. In May, Andy Burnham, the mayor of Manchester, warned that the first national lockdown was being lifted too early for parts of England where infection rates lagged several weeks behind the capital’s. A month later, the R rate in his city rose above one. The new tier system is intended to give local elected officials a greater say in the rules that will be imposed during the second wave, but it is not clear how this will work in practice. Over the weekend, as newspapers reported the outline of Johnson’s new approach, Lisa Nandy, a Labour Member of Parliament for Wigan, which is part of Greater Manchester, told the BBC that her constituents felt both abandoned by the government’s neglect during the summer and conspired against by new restrictions going into the winter. “I haven’t felt anger like this towards the government since I was growing up here in the nineteen-eighties,” she said.

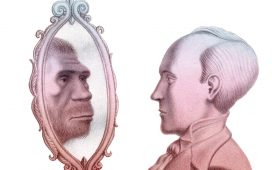

About a year ago, I spent weeks shadowing Johnson as he used his undoubted charisma, and a measure of duplicity, to secure a Brexit deal with the European Union that many people thought was unobtainable. He changed the political space around him, outmaneuvering right-wing ideologues in his own party, Jeremy Corbyn’s lead-footed Labour opposition, and centrists everywhere. When the pandemic hit, Johnson was arguably at the peak of his powers. Britain’s first case of the coronavirus was confirmed on January 31st, the day the country left the E.U. But the virus has been merciless in its exposure of Johnson’s limits as a politician and of his government as a whole. Since his own recovery from COVID-19, in April, the Conservatives have seen a twenty-six-point lead over Labour in the opinion polls disappear. Public approval of the government’s coronavirus strategy has been halved, to thirty-one per cent. The pandemic is a wicked problem, and Johnson is particularly ill suited to its demands. He abhors detail and never likes to choose. He has been unable to counter the crisis without making exorbitant promises that he cannot deliver, whether about developing a “world-class” test-and-trace program; or “Operation Moonshot,” a plan to test ten million people a day for the virus by next spring; or much-heralded announcements, like the one about the new tier system, which make a lot of noise without meaning much at all. “This is not how we want to live our lives, but this is the narrow path we have to tread,” Johnson told the House of Commons on Monday, as he described his attempt to limit both the human cost of the pandemic and the economic trauma of shutting down businesses and communities. On Tuesday, the U.K. recorded a hundred and forty-three deaths, its highest daily total since early June. It is possible that Johnson has found a narrow path that will lead to neither of those things.