The Italian government enforcing its nationwide lockdown measures to control the spread of the coronavirus outbreak.

Photo by Stefano Mazzola/Awakening/Getty Images

Your posts on social media have been harvested for advertising. They’ve been taken to build up a massive facial recognition database. Now, that same data could be used by companies and governments to help maintain quarantines during the coronavirus outbreak.

Ghost Data, a research group in Italy and the US, collected more than half a million Instagram posts in March, targeting regions in the country where residents were supposed to be on lockdown. It provided those images and videos to LogoGrab, an image recognition company that can automatically identify people and places. The company found at least 33,120 people violated Italy’s quarantine orders.

Andrea Stroppa, the founder of Ghost Data, said his group has offered its research to the Italian government. Stroppa doesn’t consider the social media scraping to be a privacy concern because researchers anonymized the data by removing profile and specific location data before analyzing it. He also has public health on his mind.

“In our view, privacy is very important. It’s a fundamental human right,” Stroppa said. “However, it’s important to give our support to help the government and the authorities. Hundreds of people are dying every day.”

Italy has become the new epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak, reporting more than 6,000 deaths from the pandemic and over 63,000 confirmed cases. To help reduce the number of cases, the Italian government issued lockdown orders that close non-essential businesses and ban movement inside the country.

Tech companies have also joined the effort, with mobile providers like Vodafone offering heat maps of location data in the country.

Government actions that would be considered privacy concerns in normal circumstances are becoming acceptable during the pandemic. Privacy commissioners around the world have said they are lifting restrictions on data protection standards, citing emergency circumstances and saving lives as a priority.

The World Health Organization has called for ramping up technology to track the spread of COVID-19. Countries including Singapore and China have shown that surveillance tools such as tracking people by their phones are effective methods.

Still, privacy advocates question how far the governments will go bending the rules on data protection. Will these surveillance tactics be phased out, they wonder, when the pandemic is contained?

“The use of high-quality data can support the vital work of scientists, researchers, and public health authorities in tracking and understanding current pandemic,” European Digital Rights, an association of civil and human rights organizations, said in a statement. “However, some of the actions taken by governments and businesses under exceptional circumstances today, can have significant repercussions on freedom of expression, privacy and other human rights both today and tomorrow.”

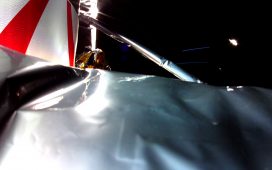

The study’s findings

The data collected by scraping Instagram Stories showed that many quarantine violations were happening across Italy.

Logo Grab / Ghost Data

Ghost Data’s researchers have mined social media for past projects, including studies about ISIS supporters using Instagram Stories to recruit new members and Russian disinformation efforts on Instagram.

In March, its researchers decided to turn their efforts to tracking Italians who were violating the country’s quarantine. Stroppa doesn’t believe they are as malevolent as terrorists or propaganda campaigns, but he thinks monitoring social media activity as a collective group has benefits for combating COVID-19’s spread.

“What we want to do is not to give the names of people or the streets where police should be, but give trends that we’ve seen,” Stroppa said. “The policymakers can use this information to change their lockdown rules.”

The research project scraped data from 552,000 Instagram profiles in Italy and gathered 504,592 Stories posted to these accounts between the dates of March 11 and March 18. Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte issued the ongoing national quarantine on March 9.

The researchers said permission to collect the data wasn’t necessary because the posts are public. Users weren’t asked to give their consent.

“Scraping people’s data violates our policies and we are investigating,” a Facebook spokesperson said in a statement. “Facebook has a number of initiatives to help combat the spread of the disease in privacy-protective ways.”

Ghost Data’s researchers stripped the posts of names, profile information, and blurred faces in photos and videos. They gave general regional data as opposed to specific locations. The data was stored in an encrypted database that LogoGrab had access to.

LogoGrab is an image recognition company based in Italy that uses artificial intelligence to spot when its clients’ brand images are being used without permission online or in counterfeit products.

The company turned its AI on the more than half a million pictures and videos that had been gathered. The AI was tasked with detecting people walking in groups and in areas such as the beach, the mall and popular city areas during lockdown orders.

The AI could determine what people were doing, like shopping, sunbathing or driving, as well as how many people were engaged in the activity. The findings called for more enforcement in urban areas, specifically near parks and beaches.

LogoGrab and Ghost Data’s report showed posts on Instagram Stories with blurred out faces roaming around Italy’s streets. Stroppa said Ghost Data has no intention of providing specific names of people violating the quarantine to the government. LogoGrab said this was up for the government to decide.

“There are circumstances, such as tracking down infected individuals, that do override individual privacy rights, for the common good, such as public health,” a LogoGrab spokeswoman said. “But those actions should only ever be sanctioned and carried out by official government agencies.”

Advocates express concerns about the use of Instagram posts in designing policy, though they acknowledge the data could be beneficial during the public health crisis.

For instance, people could upload older photos and videos from before the pandemic, suggesting people were violating the curfew when they weren’t, said Liz O’Sullivan, technology director of the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project.

“There’s always going to be a problem when you’re taking people’s private lives and using it at scale to police their action,” O’Sullivan said. “The worry is that they’ll hand this information over to the government and there will be some automated consequences linked to their behavior.”

On March 20, the Italian government issued a public call for researchers and tech companies to provide resources to help monitor and contain the coronavirus outbreak. Stroppa said he applied but hasn’t heard back yet.

If accepted, the Ghost Data founder said he would still maintain the privacy standards his company had during the study.

“We will never offer something to track individuals,” Stroppa said. “We will offer our capabilities, but only for trends, and only for anonymized and aggregated data.”

Social media scraping

Government leveraging data gathered from scraping social media is a controversial subject, but it isn’t a new idea.

Clearview AI, a facial recognition company first uncovered by The New York Times, boasts a database of more than 3 billion photos collected from social networks without people’s permission.

Like LogoGrab and Ghost Data, the company said it’s simply taking public posts that people willingly upload for the world to see. Clearview AI works with hundreds of law enforcement agencies around the world and has also been in talks to develop tracking for COVID-19.

Police have used Geofeedia, a social media analytics firm, to gather posts about protests to identify people to law enforcement.

Instagram said both Clearview AI and Geofeedia violated their data policies.

Stroppa said the data mining his researchers are doing is different from Clearview AI’s and Geofeedia’s practices. He noted that Ghost Data is a research organization and doesn’t seek to be an arm of law enforcement.

For instance, while other social media scraping efforts retain names and photos tied to the data, Ghost Data’s collection removes that information before it’s analyzed. He hopes the aggregated and anonymized data collected from Instagram will help Italian officials decide where to dedicate their resources.

“The police and other forces, even the army, are working to spot people who are in the street without a clear and effective reason,” Stroppa said. “If you see our data, there are no names, there are no locations, there are just trends. This is the balance we found between privacy and effectiveness.”

Balancing privacy and public health

Finding that balance between using technology to curb the coronavirus outbreak and protecting privacy is a key concern.

Sen. Ed Markey, a Democrat from Massachusetts, raised issues with data tracking efforts during the pandemic, warning there need to be safeguards in place on how location data is used.

When people post on social media, even when the content is public, they don’t post with the intent or awareness that the images and location data could be used by government agencies and private companies.

That’s why social media scraping leveraged by government agencies and private companies can often come as a surprise, and in some cases, violates Facebook’s data policy.

“Perhaps the posts are public, but people don’t understand that beyond the one-on-one level, these massive collection schemes are happening constantly to give corporations better understanding and ability to control people at scale,” O’Sullivan said. “How would you feel if your insurance policy was able to charge you more money because they saw on your Instagram that you were outside at the beach during the pandemic?”

The pandemic has changed how privacy is being protected, but data protection commissioners see it as a necessary step to save lives. So do the researchers gathering this data.

“When we worked on our research, we read the GDPR,” Stroppa said, referring to the General Data Protection Regulation, the European Union’s sweeping privacy law. “There is a section on the GDPR dedicated to epidemic cases and so on. It has very good thinking about this kind of situation.”

The information contained in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended as health or medical advice. Always consult a physician or other qualified health provider regarding any questions you may have about a medical condition or health objectives.