Faith Ringgold, one of the leading artists of her generation— known for the power of her engagement with the Civil Rights struggle in the US, and with feminism, and for her beguilingly illustrated and narrated children’s books—has died at home in New Jersey, aged 93.

Ringgold was known as much for the visceral quality of her political paintings of the early 1960s—her American People Series #20: Die (1967) is a landmark of US art in the 20th century—as she was for the haunting, historically charged, power of her textile narratives.

The writer and cultural critic Rebecca Carroll described Ringgold on Instagram today as “one of the greatest … to patch time and beauty, storytelling and ancestral grace together across mediums, but especially in her beautiful, astonishingly vivid quilt work”.

Writing in The Art Newspaper in 2022, the art historian Charles Moore described Ringgold as “among her generation’s most visionary and influential figures, relentlessly challenging social hierarchies, racial prejudice and gender norms”.

A daughter of the Harlem Renaissance

Born Faith Jones in 1930, in Harlem, New York City, to a sanitation truck driver father, Andrew Louis Jones, and a seamstress and fashion designer mother, Willi (Posey) Jones, she grew up at the heart of the Harlem Renaissance in the Sugar Hill district. Writers, musicians and artists such as Langston Hughes, Duke Ellington, Thurgood Marshall and Billie Holiday lived nearby and knew her family.

She was asthmatic as a child and under doctor’s orders was educated for much of the time at home until the age of eight. Her parents both encouraged her painting from an early age. She went to George Washington High School before studying at the City College of New York, earning a bachelor’s degree in art and education in 1955 and a master’s in art in 1959. For nearly 20 years, while bringing up two daughters, she taught in the public school system, in Harlem and the Bronx, and worked on her art in the evenings.

The “American People” series

Ringgold broadened her artistic training by travelling in Europe in the early 1960s and 1970s and in Africa in the late 1970s. An important staging point in Ringgold’s career was the American People series, 20 pictures produced between 1963 and 1967, at a time when she was closely involved in the Civil Rights movement. These works, which incorporate African textile patterns, marked a break with her dependence on the European masters she had studied as part of her classical training at City College.

“I became fascinated with the ability of art to document the time, place, and cultural identity of the artist,” she told The Art Newspaper in 2019. “How could I, as an African American woman artist, document what was happening around me?”

She included American People Series #20: Die, in her first one-person show at the Spectrum Gallery, in New York City, in 1967. That painting, with its clear references to Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937)—which Ringgold had studied while it was on long-term loan to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) from 1939 to 1981—was acquired by MoMA, in 2016, nearly a half-century after Ringgold had been involved in demonstrations against the exclusion of Black and women artists from that institution and from the Whitney Museum of American Art.

“I just wanted the riots, the hate, the violence to end,” Ringgold told The Art Newspaper in a 2019 interview, talking of Die. “I’ve lived through a period in America when violence would just erupt automatically—maybe in a movie theatre or coming down the street—and you didn’t know where it came from. All you knew was you’d just grab your kid and try and get the hell out of there.”

“A gut-punch of a painting about racial violence”: Faith Ringgold’s American People Series #20: Die (right) hangs with Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in a room in the Museum of Modern Art following the museum’s 2019 rehang Photograph: DPA/PA Images. Artwork: Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London; © 2024 Faith Ringgold/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy ACA Galleries

Jillian Steinhauer, reviewing Ann Temkin’s 2019 rehang of the Museum of Modern Art in The Art Newspaper, wrote: “In the New York Times, Holland Cotter called the placement of Faith Ringgold’s American People Series #20: Die (1967), a gut-punch of a painting about racial violence, near Picasso’s landmark Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) ‘a stroke of curatorial genius’; I agree.”

Ben Luke, reviewing the best shows of 2023 for The Art Newspaper, picked out the “transcendent” Faith Ringgold: Black is Beautiful, at the Musée Picasso, in Paris, a slightly smaller version of a retrospective, Faith Ringgold: American People, held at the New Museum, in New York, in 2022. “The presence of Ringgold’s gut-wrenching Civil Rights tour de force, American People Series #20: Die in Paris,” Luke writes, “where Picasso painted the work that inspired it, Guernica (1937), encapsulated the exhibition’s emotional power.”

The public activist

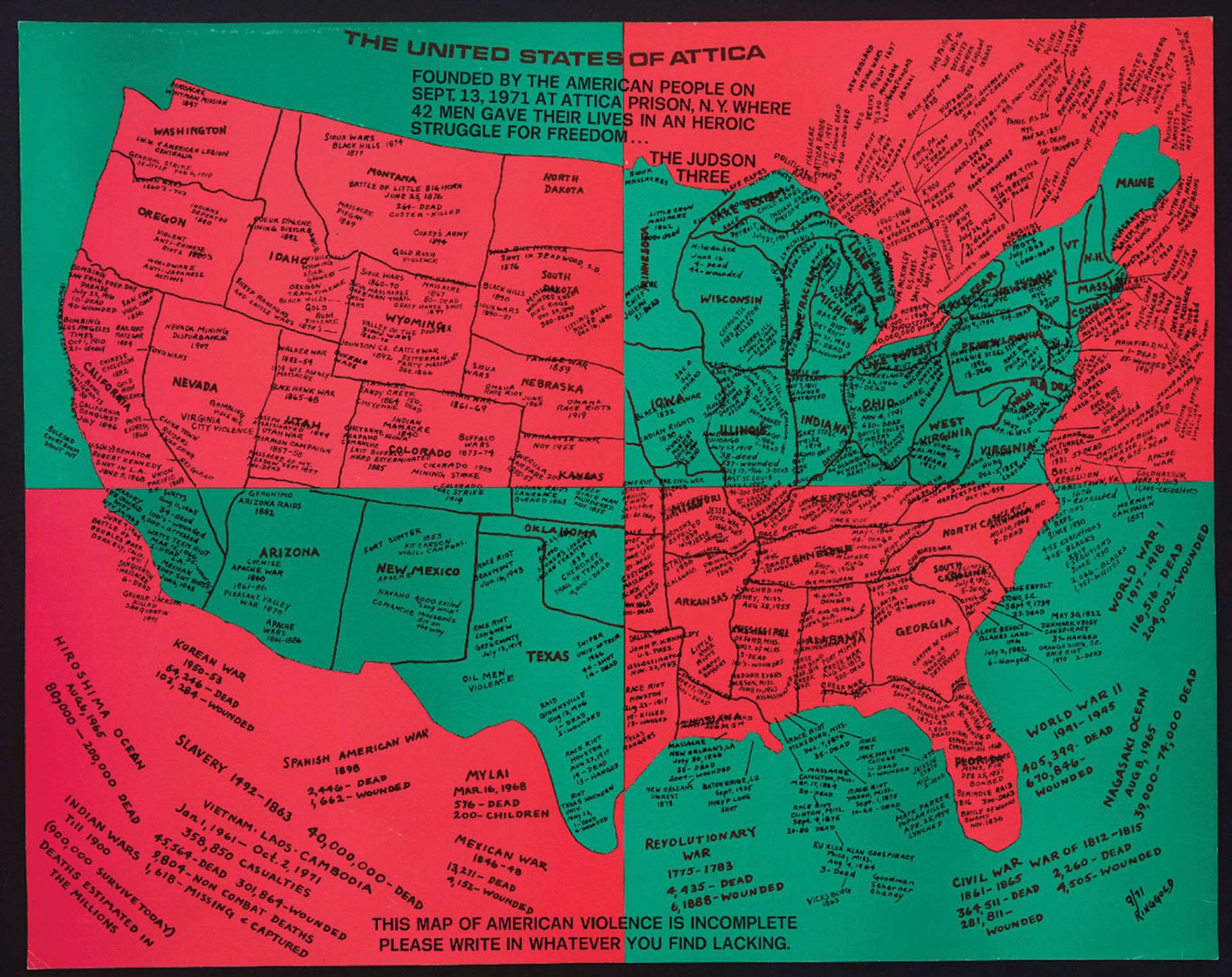

Ringgold was a noted activist in Black and feminist causes in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1970 she co-founded the Ad Hoc Committee of Women Artists with Lucy Lippard, Poppy Johnson, Brenda Miller and later Nancy Spero. The group held strikes, demonstrations, protests, sit-ins, happenings, largely at MoMA and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In the same year Ringgold was one of the “Judson Three” convicted and fined $100, along with her fellow artists Jean Toche and Jon Hendricks, for desecrating the American flag in their exhibition The People’s Flag Show, held at the Judson Memorial Church in New York. The conviction and fines were later dismissed. In 1971, Ringgold co-founded Where We At, a group for Black women artists which emerged out of a show of the same name organised by 14 Black women artists at the Acts of Art Gallery in Greenwich Village.

Ringgold created United States of Attica (1972) to honour the men who died in the Attica prison demonstration © Faith Ringgold/ARS, NY and DACS, London; courtesy of ACA Galleries, New York

Ringgold’s best-known works include two public commissions for her home city. In 1971 she made For the Women’s House, a portable mural for the women’s facility at Rikers Island. After that building became a male facility in 1988 the painting was ultimately reinstalled in the new women’s prison, the Rose M. Singer Center, and is due to go on long-term loan to the Brookyln Museum. A pair of large mosaic murals, Flying Home: Harlem Heroes and Heroines (Downtown and Uptown), created in 1996 for the 125th Station subway stop in Manhattan, shows celebrated Black figures including Dinah Washington, Zora Neale Hurston, Sugar Ray Robinson and Josephine Baker. The work’s title comes from a Lionel Hampton song that Ringgold knew as a child. “I wanted to share those memories, to give the community—and others just passing through—a glimpse of all the wonderful people who were part of Harlem,” Ringgold said. “I wanted them to realise what Harlem has produced and inspired.”

Textiles and quilts

Ringgold discovered Tibetan thangkas—18th century scroll paintings on linen or cotton—in the early 1970s, during a visit to the Rijksmuseum, in Amsterdam. “I used some of their forms to create my own Tibetan style,” she told The Art Newspaper in 2019. In the same period she started work on soft sculptures and masks. She had been inspired by African art since the early 1960s but it was not until she travelled to Nigeria and Ghana in the last 1970s, according to her own website, that she witnessed “the rich tradition of masks” that remained “her greatest influence”.

Ringgold’s work with quilts followed that with thangkas. Collaborating with her mother, who taught her to sew her paintings on unstretched canvas on to a separate cloth backing, she made her first, Echoes of Harlem, in 1980, and her first story quilt, Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima? in 1983. These works and the series that followed reference the quilting traditions of enslaved Africans, deeply rooted in Ringgold’s own family history. “My mother was a fashion designer,” Ringgold told The Art Newspaper in 2019. “She made all our clothes and then went into business herself when we got older. She learned how to sew from her grandmother, who had in turn been taught by her mother—they were born slaves and had been quilters all their lives.”

“But I don’t make quilts the way other people do,” she told The Art Newspaper, “my images are all painted. I paint on canvas and then I sew the painting onto other backings. Canvas is just a textile, whether or not it is stretched on stretcher bar.”

Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima? was created as a direct response to publishers who had rejected the typescript of her memoir. At a solo exhibition at the New Museum in New York in 1998 Ringgold showed two notable series of her story quilt paintings: The French Collection, and the American Collection, which she also presented in her 2022 retrospective at the New Museum in New York. “The French Collection uses the character Willia Marie Simone to re-centre the story of Modern painting,” Charles Moore wrote in his review of the exhibition for The Art Newspaper. “She visits the Louvre, meets Van Gogh in Arles, sits for Matisse and Picasso and ultimately ends up a successful artist herself. The American Collection, meanwhile, imagines the paintings of Marlena, Willia Marie’s adult daughter, herself an artist, but in the US, and looking at African American cultural history including, among other things, slavery.”

The story-teller

Ringgold was the author of more than a dozen engaging children’s stories, starting with her acclaimed Tar Bridge (1992), which was inspired by her own story quilt Woman on a Bridge #1 of 5: Tar Beach(1988), now in the collection of the Solomon R Guggenheim museum in New York City. The quilt shows Cassie Louise Lightfoot—who, we discover in the 1992 book, was born one year and 17 days after Ringgold, on 25 October 1931, the day the George Washington Bridge, in New York City, opened—and her family on their Harlem rooftop, their “tar beach”.

Cassie sleeps out at night on the tar beach and one summer night she takes flight over the George Washington Bridge, watched by her baby brother, while her parents and their friends play on, oblivious, at cards. After flying over the bridge, Cassie says in the book, she owned it and “could wear it like a giant diamond necklace”. “My women,” Ringgold said of the Women on a Bridge series, “are actually flying; they are just free, totally. They take their liberation by confronting this huge masculine icon—the bridge.” The title of We Flew over the Bridge: The Memoirs of Faith Ringgold (1995) is a clear reference to the author’s best-known work of children’s fiction.

Ringgold, who had used the surname of her late second husband, Burdette Ringgold, since their marriage in 1962, had two daughters with her first husband Robert Earl Wallace: Barbara Wallace, a linguist, and the writer and cultural critic Michelle Wallace, author of Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1979).

Ringgold remained an educator for nearly a half-century after she first taught in New York schools, teaching at the Pratt Institute in the city, and was latterly professor emeritus of art at the University of California, San Diego. Her work is in the collections of institutions including the Art Institute of Chicago; the Boston Museum of Fine Art; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; and the Victoria and Albert Museum, in London.

From 1995 she was represented worldwide by the American Contemporary Art Gallery (ACA Gallery) and her other notable solo shows include those at Studio Museum, Harlem, New York, in 1983; the Fine Arts Museum of Long Island, in 1990, which toured nationally to 11 other museums; the Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase, New York, in 2010; and Serpentine Galleries, London, in 2019.

- Faith Willi Jones; born New York City 8 October 1930; married Robert Earl Wallace (died 1961, two daughters, marriage dissolved 1956), 1962 Burdette Ringgold (died 2020); died Englewood, New Jersey, 13 April 2024.