The British artist David Shrigley has returned to his Midlands secondary school almost 40 years after graduating to unveil an animatronic sculpture of a giant praying mantis, in the hope that it will spark a nationwide conversation about the “vital importance” of arts subjects.

Mantis Muse, a three-metre-tall sculpture made from steel and fibreglass, was unveiled today (28 October) to pupils at Beauchamp College in Oadby, where Shrigley studied between 1983 and 1987. During its two-week stint on campus, the sculpture will be the focus of life drawing, biology and yoga classes, among others.

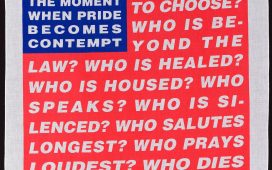

Since 2010, when the Conservative party came to power, the number of children studying art at GCSE level has halved nationally, while enrolment for art A-levels has fallen by a third. During 14 years of Tory rule, Stem (science, technology, engineering and maths) subjects were championed and funded to the detriment of the arts. Shrigley thinks that, without the arts, “an education is not a full one”. He adds: “We know that an engagement with the arts is valuable to people’s health and well-being, and, in real economic terms, investing in art and culture reaps dividends. But in terms of an education, if you’re going to be an engineer, you also need to think creatively.”

The artist praised Labour culture secretary Lisa Nandy for her recent interview in the Guardian in which she said a balanced education must also include arts subjects, though Shrigley acknowledged it will be difficult to reverse 14 years of Tory policy in one term in government.

Recalling his time at Beauchamp College, where the artist studied art, English literature and sociology at A-level, Shrigley says he “really enjoyed” his studies after he’d chosen to take arts subjects. “I wasn’t super academic, I ended up just passing my exams,” he says. “But I had a couple of teachers who inspired me a lot, and one in particular, Chris Tkacz, who was an artist—he’s still an artist. He pushed me to go to art school. He was really encouraging and had a positive impact on me as a kid at that age.”

Mantis Muse echoes a number of other “life model” sculptures Shrigley has made in the past, most notably the installation he made for the 2013 Turner Prize, of a nude sculpture of a disproportioned man who occasionally urinated into a bucket. Easels were set up around the sculpture and people were invited to draw the animatronic figure, though it caused some controversy in schools in Northern Ireland who declined invitations to view the show.

“It occurred to me that this project was sitting around in my mind, I wasn’t really sure what it was—it’s a continuation, and odd deviation, of other things that I’ve done,” Shrigley says. “The project was originally intended to be in a gallery or museum situation, but it just never worked out for one reason or another. I ended up deciding to want to do anyway, thinking it could be a very different work if I put it in a school. To put it in my school gave me this opportunity to tell a story about my art education and how much that meant to me.”

Aside from the message about the importance of an arts education, Shrigley says making a work about a praying mantis—“the coolest insect that looks like something from another planet”—speaks to the climate crisis. “It’s very easy to see polar bears stranded on ice flows in the Arctic and orangutans with no habitat to live in, but insect life is a far more pertinent reminder of what we’ve done to this planet,” he says. “We don’t really pay attention to it because it’s not that visible. But what’s happened in terms of insect life on the planet is really, really alarming. Insects are hugely important creatures—they are the most numerous creatures as a species on the planet, and we’ve destroyed half of them.”