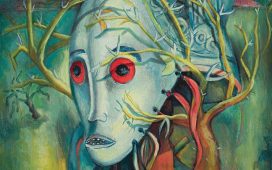

Amateur dramatics: Julio Agostinelli’s Circus (Circense) (1951) will be on show at MoMA

© 2016 MoMA, NY, © 2020 Estate of Julio Agostinelli.

A prolific but little-known collective of Brazilian amateur photographers from the mid-20th century is the subject of a new show at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York this week. The Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante (FCCB)—which primarily included hobbyists, but also established artists such as José Oiticica Filho and German Lorca—was founded in São Paulo in 1939 and produced captivating work that remains largely unseen by audiences outside Brazil. The show will comprise more than 60 photographs that reveal “a chapter of art history that has been woefully neglected”, says the MoMA photography curator Sarah Meister.

“Re-evaluating the status of the amateur is one that holds promise for recuperating other aspects of photography’s history”

Sarah Meister, photography curator, MoMA

The FCCB has a compelling relationship with MoMA dating back to 1948, when Thomaz Farkas—a founding member of the FCCB—travelled to New York and met Edward Steichen, then the director of the photography department. Two photographs Farkas made during his visit were included in his first solo exhibition at the Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo. He also sent Steichen prints that he hoped the director would find “technically suitable”. Steichen included one of them in the 1951 show Abstraction in Photography. The others were virtually forgotten and only catalogued in 2014 as part of an initiative to broaden the understanding of MoMA’s collection, during which it acquired more works by the group.

Thomaz Farkas’s Ministry of Education (Ministério da Educação) (around 1945)

Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the artist

Meister says there are perhaps two biases to blame for the FCCB’s lack of recognition. “The first is historical neglect of artistic achievements originating from the so-called ‘periphery’,” she says. “And the second is the presumption that amateur photographic practices are hopelessly imitative—meaning that to pursue photography as a hobby is inimical to original creative achievement.” She adds: “The act of re-evaluating the status of the amateur is one that holds promise for recuperating other aspects of photography’s history—and many other neglected histories.”

Works such as Filigree (Filigrana) (1953) by Gertrudes Altschul, which shows the delicate surface of a papaya leaf, provide “an unusual example of a connection between an FCCB member’s day job—she made artificial flowers for millinery—and their choice of what to photograph”, Meister says. Other works show abstracted visions of domestic and everyday scenes, such as Maria Helena Valente da Cruz’s The Broken Glass (O Vidro Partido) (around 1952).

Maria Helena Valente da Cruz’s The Broken Glass (O Vidro Partido) (around 1952)

Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired Donna Redel. © 2020 Estate of Maria Helena Valente da Cruz

Meister adds that amateur photo graphy began in the late 1880s, when the Kodak No. 1 made the medium democratic, an ever-relevant concept when “everyone has a camera in their pocket at all times”, she says. “We may have substituted ‘likes’ for the scorecards and stamps of approval on the versos of many of these prints, but we are asking the same question: what makes a good photograph?”

• Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946-64, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 8 May-26 September