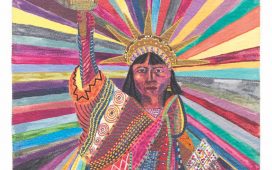

The Middle Eastern financier Mohammed Afkhami is putting his collection of Modern and contemporary art by Iranian artists on public display once again. The exhibition Rebel, Jester, Mystic, Poet: Contemporary Persians is due to open at the Asia Society in New York this autumn (10 September-16 January 2022), featuring works by 22 artists including Farhad Moshiri, Shirin Aliabadi and Afruz Amighi; the touring show has already been seen at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

This time though, the political context is different. When the show opened in Canada in January 2017, it coincided with Trump’s controversial travel ban targeting travellers from mainly Muslim countries. “The timing is very good for a couple of reasons: New York should be fully open from July and the US is driving ahead with its vaccination programme. The Biden administration and the Saudi government are keen to come to an accord with Iran; it’ll come to a head around the UN meeting due to take place late September in New York. This gives the exhibition a topical perspective,” Afkhami says.

Mohammed Afkhami with a work by Khosrow Hassanzadeh, Terrorist: Khosrow (2004), from his collection

Mohammed Afkhami Foundation

The revolution happened and the collection was confiscated; bits even started appearing in auction rooms in the early 1980s. The revolution was a wipe-out event but art has been a lifesaving and eternal part of the family

Mohammed Afkhami

The Swiss-born Afkhami divides his time between Dubai, Switzerland and London. He spent his childhood in Tehran, but his mother left Iran after the Islamic revolution in 1979. He began buying art in 2005, acquiring works by Sirak Melkonian and Massoud Arabshahi from Mah Art Gallery in Tehran. His collection includes around 600 contemporary and Modern works, mostly from Iran; other artists represented include Mohammad Ehsai, Shirin Neshat, Shiva Ahmadi and Timo Nasseri.

Afkhami’s paternal great-grandmother, Effat al-Muluk Khwajeh Nouri, was the first female artist in Iran to set up a private painting school for girls. His maternal grandfather, Mohammad Ali Massoudi, compiled one of the most significant private collections of calligraphy in Iran (some examples were exhibited in 1978 at the Reza Abbasi Museum in Tehran, founded in 1977 under the auspices of Queen Farah Pahlavi).

“The revolution happened and the collection was confiscated; bits even started appearing in auction rooms in the early 1980s. The revolution was a wipe-out event but art has been a lifesaving and eternal part of the family,” he says, stressing how Iran’s centuries-old art and heritage underpins its contemporary culture. “The Safavid (1501-1736) and Qajar (1794-1925) periods have influenced 20th-century art; everything is connected. Works made in Iran today are inextricably linked to the past.”

Alireza Dayani, Untitled (Metamorphosis series) (2009)

Mohammed Afkhami Foundation

Afkhami has been busy over the past year. When most of the world went into lockdown last spring, he decided to support the Iranian art scene by sourcing works directly from the country. “A year ago when sanctions were getting really bad in Iran, I thought that one way to give back to these artists in a dignified way was to buy works by emerging artists in Iran. I opened an account with Dastan’s Basement gallery in Tehran and added about 60 new works. We bought artists, new and old, that had either been forgotten or not represented. We paid in US dollars in a currency that had spiralled downwards.”

As co-chair of the Guggenheim’s Middle East and North African art acquisition committee, he also helped oversee a major acquisition for the museum: a painting from the Shit Moms series (2019) by Tehran-born Tala Madani. “It’s a great time to be buying works from the Middle East, the prices haven’t collapsed. There’s a renewed interest in the region. I’ve seen it with the museum committees; they’ve very active, they’re buying,” he says.

He was at Art Dubai in March, which he says could be a model for how fairs operate in the wake of Covid-19. “People were monitored at the fair, it was very social. Every time a cluster of four or five people formed, they [fair security] would be in there busting it up. But it worked. It reminded people that it’s still very much a physical business.” Post pandemic, he will follow strict self-imposed guidelines. “I’m not going to be in New York [for Frieze] but I would go. I’ll go to any fair in any country where the majority of people have been vaccinated. That’s my rule.”

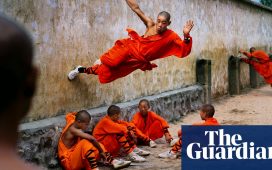

Rokni Haerizadeh, We Will Join Hands in Love and Rebuild our Country (2012)

Afkhami is also building a “virtual museum”, ploughing his cash into an ambitious online platform which will initially showcase his own collection and other holdings in time. The new website, which should be ready by the end of the year, will also incorporate scholarly texts and a special feature enabling viewers to see inside the studios of Iranian artists.

“It’s going to be unbelievable. I’ve mandated that this should be accessible to people in Iran with a mobile connection as low as 3G. It has to be seamless and able to be supported by any current bandwidth,” he says. “The annual maintenance [of the virtual museum] costs hundreds of thousands rather than millions. You can have many more visitors than you ever would in a physical space.”

The Asia Society show will be meanwhile a welcome opportunity to re-visit one of the world’s most comprehensive collections of Middle Eastern art. But the new online portal should also be an essential resource. “It will be a real window into Iran and its artists,” Afkhami says.