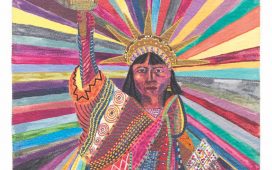

Peter Kennard and Cat Phillipps, Photo Op (2007)

© kennardphillipps

For decades, the British artist Peter Kennard created and distributed his punchy political photomontages protesting against nuclear weapons, apartheid and anti-European policies, among other issues, in newspapers or on fly posters in the street.

But now, for the first time in 15 years, Kennard has won commercial representation, joining Richard Saltoun Gallery in London, where his exhibition opens next month. Part of a year-long programme celebrating the influence of the German political theorist Hannah Arendt, Kennard’s show includes his early STOP paintings, created between 1968 and 1976, as well as Pallet sculptures from the 1990s and a new series of works on paper created during lockdown (prices range from £10,000 to £60,000).

Kennard’s cut-and-paste technique began around 1967, the year he started at the Slade School of Fine Art in London. At that time he was going on demonstrations against the Vietnam War. He says: “I started to use photographic images in relation to making work, to record the civil rights movement, the war and the May 1968 student riots in Paris.”

Some of Kennard’s best-known work followed his STOP paintings, such as Haywain with Cruise Missiles and Protest and Survive, both from the 1980s. The former was, Kennard says, a “resistance to the imminent stationing of cruise missiles in the English countryside”. In the work, Constable’s bucolic scene is interrupted by enormous weapons protruding from the horse-drawn cart. Kennard’s version was made into a postcard, which the artist used to take into London’s National Gallery and slip into piles of postcards of Constable’s actual painting—a forerunner to Banksy’s pranks (the Bristol street artist has paid tribute to Kennard who worked with Banksy in Bethlehem in 2007).

Artist as activist

As with much of Kennard’s work, his art spills over into activism. In 2011, he took part in protests at the National Gallery over its sponsorship by Finmeccanica, one of the world’s largest weapons manufacturers. A year later the arms firm dropped its sponsorship, only to reappear seven years later under the name Leonardo. The newly rebranded arms dealer then held an event at the Design Museum in 2018, sparking further controversy and the removal of works from the museum by artists.

Kennard has applied his sardonic approach to art-making to wars in Chile, Northern Ireland, Palestine and the Gulf, among others. Such work has earned him the moniker of “unofficial war artist” as well as “Britain’s most important political artist” from Richard Slocombe, the Imperial War Museum’s senior curator.

In 2007, Kennard returned to photomontage to create, with Cat Phillips, the now-famous image of a grinning Tony Blair taking a selfie in front of a blazing oil field in Iraq, titled Photo Op.

The image was so plausible, many thought it real. “When you make a montage you never legislate for what’s going to stick or what isn’t,” Kennard says. “When we did it, it just seemed like another image but that one really stuck. Google it and it still turns up. It must be very annoying for Blair.”

As for showing in a gallery again, Kennard is enthusiastic. He says: “I’ve always thought it important to show in galleries, mainly public galleries, because historically they have been quite happy to not have any political work on show, especially in this country. But that is beginning to change, at last.”

Gallery owner Richard Saltoun points out that Britain has a strong history of art and culture with left-wing political values, “however, since the 1990s—in part due to the explosion of the art market—the direct involvement of visual artists in politics has waned”.

Saltoun adds: “It is clear though that Peter is out of time, he has fallen into an odd space, between artist, professor, activist and political force. For this reason he seems to fallen into a ‘gap’, slightly lost, and written out of the institutional story of post-war British Art.”

In 2021, that history is finally beginning to be rewritten.

• For an interview with Peter Kennard on the influence of Hannah Arendt, listen to our podcast The white supremacist art at the heart of the US Capitol