Give me a ladder to climb—the jungle gym of the corporate org chart, the hazy inner ranks of some large church, the series of badges and pins upon which military order is maintained—and I can spin out a story about America. Hierarchy is our great imaginative canvas. We don’t want to know just about the inner workings of the mob, but also about how the one guy became the boss; follow not just baseball but the World Series; if the hero’s a priest, he’d better have a plan to be Pope. Tell us how you survived, sure, but also how you got over.

There’s a technical aspect to this narrative preference: upward motion feels like forward motion, and success has beats that are easy to chart and make propulsive. But the deeper issue is moral—against our higher instincts, and despite the ample evidence of experience, we stow away a pinch of belief that there’s more freedom at the top of the pile.

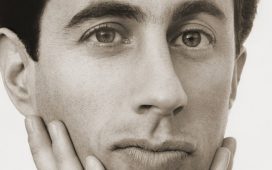

Charles Fuller’s “A Soldier’s Play”—which débuted in 1981 and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1982—is obsessed with signs of seniority. Thwarted advancement makes the piece move. The play, which has been revived by the Roundabout Theatre Company, at American Airlines Theatre, under the direction of Kenny Leon, takes place in the mid-nineteen-forties, on a segregated Army base in Louisiana, where a black sergeant, Vernon Waters (David Alan Grier), has been mysteriously killed. Everybody blames his death on the Klan, but nobody seems to really know what happened. Waters, whom we glimpse in flashbacks that bleed into the present investigation of his death, is a proud, haughty, casually abusive man who wields his rank as a bludgeon and whose humor—Grier’s well-honed specialty as a performer, now spiked with rancor—is a firearm trained on the soldiers under his command. He’s a bully; Grier makes his malice terrifying, but also seductive.

Waters has it in for the Southerners in the regiment. Their regionalisms and humble folkways—songs and jokes, manners refined and reinforced by fear of violence and, often, death—seem to him mere bowing and scraping and jiving at the feet of the white world. Waters thinks these men are holding blacks back with their levity and obeisance. Better, he thinks, to rise within the white man’s meritocracy and eventually subvert it on its own terms. He’s a perverse opposite of the great writer and activist Audre Lorde, who warned that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” Notions of uplift, shorn of love, have made him a husk. His ascent within the military is, to him, an accrual of human dignity; he uses official discipline—taking away one man’s hard-earned “stripes” over a trifle, sending another man to military jail—to strip others of their dignity.

Yet, for all his grasping, he lacks the respect that his success was supposed to win. Even his pettiest order can be reversed by Captain Taylor (Jerry O’Connell), the white man who’s the head honcho on the base. Waters hates just about everybody, but especially a private named C. J. Memphis (J. Alphonse Nicholson), a star baseball player who sings the hell out of the blues and wins more favor from whites by way of his talent than Waters does by his rank. (This implicit dismissal of art rings true even today; Waters is a bit like the contemporary corporate striver who brags about never cracking open a work of fiction.)

There are two plays here: the interstitial telling of how Waters’s wickedness, born of racism and spurred on by sheer spite, sends him spiralling downward, toward the grave; and a much more rote detective story about how his killer is caught. “A Soldier’s Play” is weakest precisely as it strains to transition between these two strands: there are awkwardly choreographed scene changes performed by the privates, and work songs that are effective on their own but not necessarily as the hinges they’re meant to be.

Blair Underwood plays Captain Richard Davenport, a black man who has come to the base to sift through the facts. He inspires derision from Captain Taylor, who just can’t get used to the sight of a black officer (not to mention one who wears sleek dark aviators indoors), and awed reverence (salutes and grins and slyly happy repetitions of his title, Captain) from the blacks who are gratified to see a version of themselves represented in so starchy a shirt, such an impeccable tie. Davenport’s rank kicks up almost as much chaos as Waters’s death.

Underwood is fine in the role, but his is by far the cornier half of the proceedings. There’s too much focus on his relationship, and eventual fraught reconciliation, with Taylor, and too little on what’s behind the anguished howl he belts out after he’s broken the case. There could be a terser version of this show whose focus is all on Waters, and on the inner decline that accompanies his professional advance. Grier plays the sergeant with a pleasing near-incoherence, his splashes of anger and despair always threatening the arrival of fiercer waters. One minute he charms and the next he bites. He flexes his face into pantomimes of unspeakable cruelty and turns his roly-poly body into a harbinger of constant threat.

Waters’s final words are the first ones we hear spoken: “They still hate you!” —it’s the truth as a taunt. The range and precision of Grier’s voice makes his upper registers citrusy and substantial, and his lower tones ragged, like the sound of a blown-out subwoofer. The multivalence of that voice, and of Grier’s entire performance—now comic, now inviting doom, and, finally, much too late, sodden with remorse—gives his moments onstage their bitter, dismal truth: upward motion means nothing when your ceiling is somebody else’s floor.

“Timon of Athens,” William Shakespeare and Thomas Middleton’s brusque tale of hard luck, directed by Simon Godwin at the Theatre for a New Audience’s Polonsky Shakespeare Center, is another disillusioned illustration of social position gone sour. Timon (Kathryn Hunter) is a rich woman—Hunter effortlessly pulls off the flipped gender of the protagonist, originally written as male—who is profligately generous to her friends, and who learns in the worst way that they won’t return the favor. The show opens with Timon hosting a grand dinner. Little do the revellers know that their benefactor is badly in debt. The good times are about to shudder to a close.

The sanest among Timon’s guests is the astringently philosophical Apemantus (Arnie Burton), who so scorns the display that he pulls a root vegetable and some water out of what looks to be a lunch box and plops down at a makeshift kids’ table. Despite his warnings, and those of Timon’s loyal attendants, she has spent her very last cent, and, when the bill collectors come, the rich partyers are no help. Soon, Timon, repelled by Athens and its “affable wolves,” is living on the city’s outskirts, her once sparkling whites sooty and the fun in her face gone.

The language in the latter half of the play is full of the rhetorical device chiasmus. In a typical passage, a pair of thieves come to Timon on her heath in order to “wait for certain money”; in her refusal, she inverts their syntax as well as their wishes—if only “money were as certain as your waiting.” These clever phrasings are echoed in Hunter’s astounding performance. She brings to each dense moment a platter bejewelled with ironies. There’s a wistful murmur under her act as the happy socialite; homelessness and crazily jaded misanthropy turn her into a kind of Catskills comic. (One running bit is her patter with the audience.) Hunter’s voice is low, husky, and silkily resonant, a rare instrument, and the more destitute her Timon becomes the more ardently she sings her syllables. Each of her fine gestures expresses a paradox that sits beneath the text. Her eyes rage and then melt, all in the space of a second.

There is neither up nor down, utter failure nor lasting success, for Hunter’s wind-tossed Timon—only the person nearly naked, cast away and caught in life’s centrifuge. No great nation, or battalion, or sign of status is relevant to existence at the city’s peripheries: better to search for higher loves and find a friend or two. ♦