In the summer and autumn of 1974, more than 50 sculptures by a veritable who’s who of Modern art—including Alexander Calder, Willem de Kooning, Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore, Louise Nevelson and Christo—took over the buttoned-up, coastal town of Newport, Rhode Island. An event of this magnitude would surely go down in the annals of art history for perpetuity, so why is it that Monumenta, this landmark public sculpture show, has faded into relative obscurity?

Fifty years later, the exhibition’s co-organisers and the Preservation Society of Newport County are working to reaffirm its legacy. On 17 August, the Preservation Society hosted a celebratory event at Rosecliff, one of its 11 historic properties, to shine a light on the exhibition’s story and impact, and to announce new initiatives to safeguard its legacy. Filling Rosecliff’s opulent, oceanfront ballroom to the brim, attendees wore their Monumenta pride like a badge of honour—though that was by no means how the show was received at its inception.

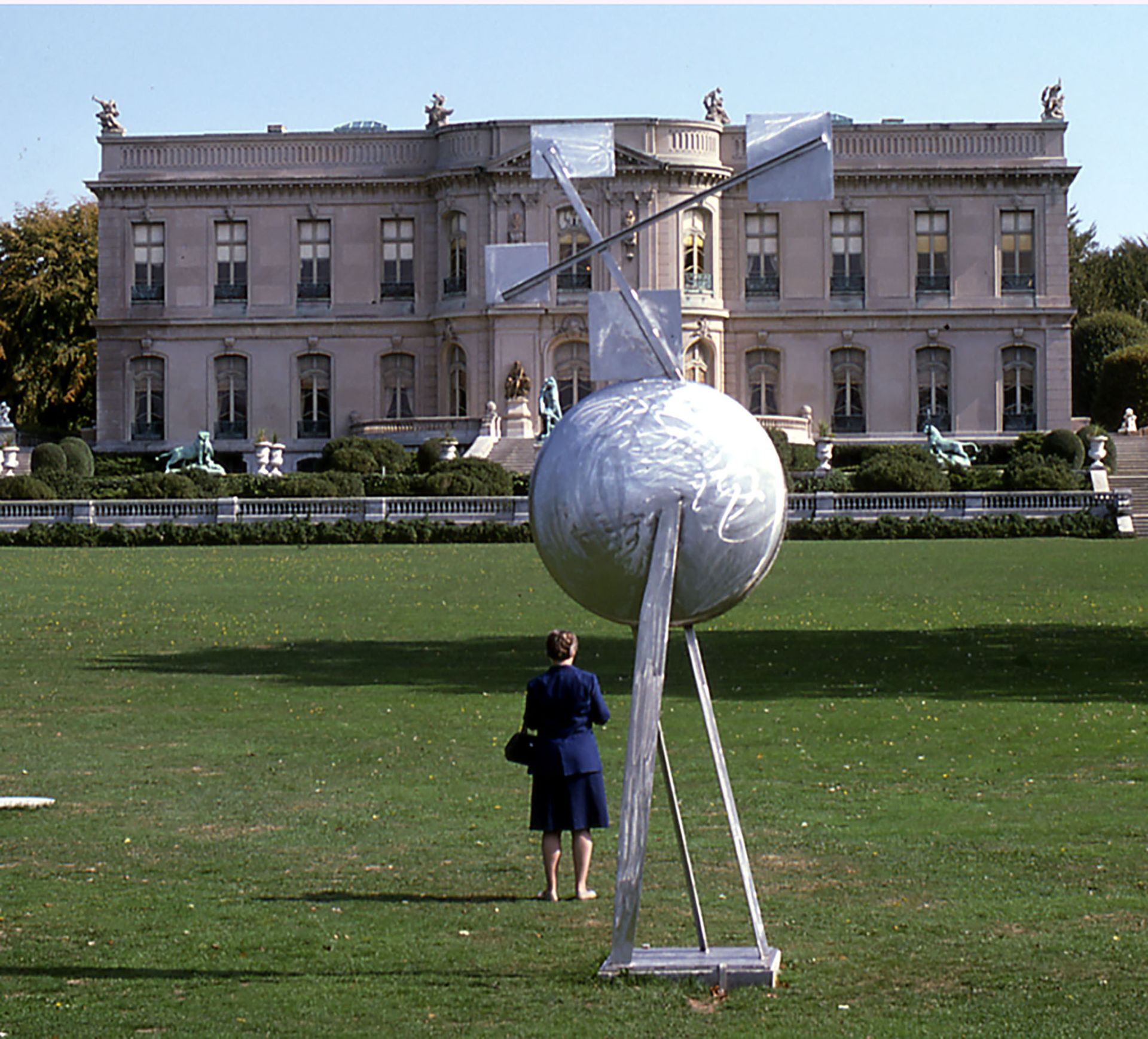

David Smith’s Windtotem (1962)installed at The Elms during Monumenta Photo by Nancy Rosen

“When we were installing these pieces, people would drive by and hurl insults, like ‘I hope you’re not leaving that piece of junk on Ocean Drive’,” says Hugh Davies, the director emeritus of the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, in reference to Claes Oldenburg’s Geometric Mouse (1969). Davies co-organized Monumenta as part of the art history professor Sam Hunter’s PhD graduate seminar at Princeton University. “For Newport’s traditional and conservative crowd, it was an atrocity to bring this ‘ugly’ new art to Gilded Age properties that were very much of their moment. Many people thought Modern art was a joke.”

At the same time though, public art programmes were being pushed on a federal level as a means to enrich urban spaces—in 1967, for example, Calder’s La Grande Vitesse for the City Hall plaza in Grand Rapids, Michigan, became the first public art piece to be funded in part by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA).

Alexander Liberman, Argo (1974), on view during Monumenta Photo by Nancy Rosen

A year prior to Monumenta, Hunter, who had an illustrious editorial and curatorial career that included serving as director of New York’s Jewish Museum, curated a public art exhibition in Boston. This Modern sculpture show caught the attention of the real-estate developer Jay Schochet, who wanted to do something similar in Newport. Shochet introduced Hunter to William A. Crimmins, a Newport resident, passionate about the arts, who would ultimately fund the bulk of Monumenta (the project also received an NEA grant). Crimmins also provided Hunter’s team with crucial connections, most importantly to Katherine Warren, the co-founder and first president of the Preservation Society, and a serious Modern art collector. With Newport set to host the America’s Cup sailing yacht competition in 1974, staging a concurrent showcase of Modern art would further enliven the city and impress the legions of tourists.

Spectacle on a shoestring

Monumenta was made possible by Hunter’s relationships with artists and institutions, and Crimmins’s and Warren’s Newport clout. Also crucial was Hunter’s young and scrappy team, which included students from his PhD graduate seminar like Davies, as well as the recent Brown graduate Nancy Rosen, whom Hunter knew from his time as an editor for the art publisher Harry N. Abrams, where she worked. As part of the seminar, Davies led the curation for Monumenta, while Rosen managed logistical responsibilities, such as insurance, shipping and correspondence.

Christo, Ocean Front Project at King’s Beach, Newport 1974. Width, 420ft; depth, 320ft; 14,800 sq. yards of woven polypropylene fabric floating on the ocean and attached inland to 40 anchors. Featured in Monumenta exhibition, 1974, where it was installed at King’s Beach. Lent by the artist. Photo courtesy of William “Bill” and Gael Crimmins

“None of us were paid anything—we were just thrilled to volunteer,” says Davies, adding that “it was the most fun summer ever” staying with classmates at the Crimmins home in the months leading up to the exhibition. Like Rosen, now a New York City-based curator who manages fine art collections and public art programmes, including for Manhattan’s Battery Park City, Davies emphasises how much the experience shaped his career: “It’s the reason I ended up going into museum work rather than teaching because I loved the contact with the artists and objects.”

Davies’s favourite memories from the project include returning De Kooning’s sculpture, Clam Digger, to the artist’s Long Island studio after the exhibition. Though Davies says he had never understood the work’s “diminutive” scale, it suddenly clicked when De Kooning came out to greet him. “When he stood next to it, it was exactly his height!” Davies also recalls struggling to install John Chamberlain’s ultra-light aluminium Vipers Bugloss, that is until the artist himself appeared and suggested “just drill[ing] a hole” in the bottom of it.

Willem de Kooning’s Clam Digger (1972) on display at Chateau-sur-Mer during Monumenta Photo by Nancy Rosen

All the sculptures in Monumenta were either lent by the artists’ estates, their galleries or by the artists directly. None were for sale. “Frankly, I think most of the Newport community would have been happy to pay to have the works removed,” Rosen says, acknowledging that the sculptures were hard to miss, whether they were installed on the Bellevue Avenue lawns of the Elms and Chateau-sur-Mer (where most of the heavy-hitters, including no fewer than ten David Smith sculptures, were displayed for security reasons), Fort Adams, Bowen’s Wharf or other local landmarks. Despite a glowing review in The New York Times, Rosen says most locals were “puzzled” and “bewildered”.

Jazzed about Modern art

Though Newport had a long and rich cultural history, by the 1950s its visual arts innovation paled in comparison to its musical pedigree, largely cemented by the still-beloved Newport Jazz Festival, established in 1954. “We’d say, ‘Jazz is the music of the 20th century, and this is the art of the 20th century,’” Davies recalls, adding that Monumenta’s main objective was to show “the historic bridge between traditional large-scale outdoor objects and site-specific work”.

Installation view of Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Ocean Front, 50 Years Later at the Newport Art Museum, until 29 December 2024 Photo by Tom Powel Imaging

Monumenta’s most ambitious site-specific work was Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Ocean Front Project (1974)—the duo’s first-ever covered-water piece and public work on the East Coast—which covered the cove at King’s Beach in 150,000 sq. ft of white woven polypropylene floating fabric. “It precedes Surrounded Islands in Miami and The Floating Piers in Italy, but, of course, nobody knows about the Newport work that really started it all,” says Vogue’s art world correspondent Dodie Kazanjian, who was born and raised in Newport. Kazanjian curated Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Ocean Front, 50 Years Later, featuring archival documentation gifted by the artists’ estate to the Newport Art Museum (until 29 December).

Inspired by her “wow” moment of seeing Monumenta in her youth, Kazanjian became the founding director of Art&Newport in 2017. Working closely with local institutions and the tourism board, she has helped usher in a new era of contemporary art in Newport. In 2019, for example, Nicolas Party works were installed throughout Marble House, while this past summer, The Great Elephant Migration debuted its herd of 100 life-sized elephant sculptures, made by Indigenous Indian artisans, along Newport’s Cliff Walk.

Monumenta redux?

Richard Fleischer, Sod Maze, 1974 Photo by Nancy Rosen

As for the likelihood of another Monumenta, the consensus among Davies and Rosen is that it’s possible but with a lot of local will and likely a less extensive programme. “It’s a dream and we’ve certainly considered it, but there are a lot of challenges to pulling together something on that scale,” says Trudy Coxe, the Preservation Society’s executive director and chief executive.

The co-organisers believe the key to any future sequel rests with Kazanjian and the Monumenta family, specifically Crimmins’s step-daughter, Alyson Baker. Before establishing River Valley Arts Collective in the Hudson Valley in 2018, Baker held posts as the executive director of the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut, and Socrates Sculpture Park in New York City.

Richard Fleischer, Sod Maze, 1974. Featured in Monumenta exhibition, 1974, where it was installed at Chateau-sur-Mer. Photo courtesy of Richard Fleischner

“During the 1970s, things were a lot more accessible than they are now, but I think you could certainly translate the spirit, intent and passion for the project into something that could happen today, and I’d love to be part of it,” Baker says, citing the “great groundwork that is already being laid” by Kazanjian and others. The Preservation Society has already tapped Baker to help with the restoration of the only work from Monumenta still in situ: Richard Fleischner’s Sod Maze, a permanent Land art installation on the grounds of Chateau-sur-Mer. The organisation is also directly collaborating with the Providence, Rhode Island-based environmental artist to restore the work.

Other Monumenta efforts include the Monumenta50 Archive, which will add images, oral history and more to the existing archive that William and Gael Crimmins donated to the local Salve Regina University after the exhibition. All parties agree that given the immense turnout and enthusiasm at the anniversary symposium, the appetite to preserve Monumenta’s legacy has never been higher.

“In 1974, if Newport residents took a poll, the majority would say, ‘Let’s not do this again,’” says Davies. “Now, I think people are very proud that it happened in Newport.”