On 26 October, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) opened Power of the People: Art and Democracy (until 16 February 2025), our first exhibition devoted to works of art as primary sources of democracy. Featuring 180 works from 525BC to 2020 in widely varying media—there are ceramics, stone reliefs and inscriptions, oil paintings, textiles, books, marble sculpture, fashion, prints and photography—it is drawn almost exclusively from the museum’s own holdings.

The exhibition is organised into three chapters, over three rooms: the promise, the practice and the preservation of democracy. The first looks at the way societies have idealised democracy, contrasting tidy, aspirational narratives with complicated stories. The second shows not only how democracy can work and how it looks in action, but also what doesn’t work. Finally, the third considers the importance of people’s voices in democracy—their responsibility to use it well, along with their right to it.

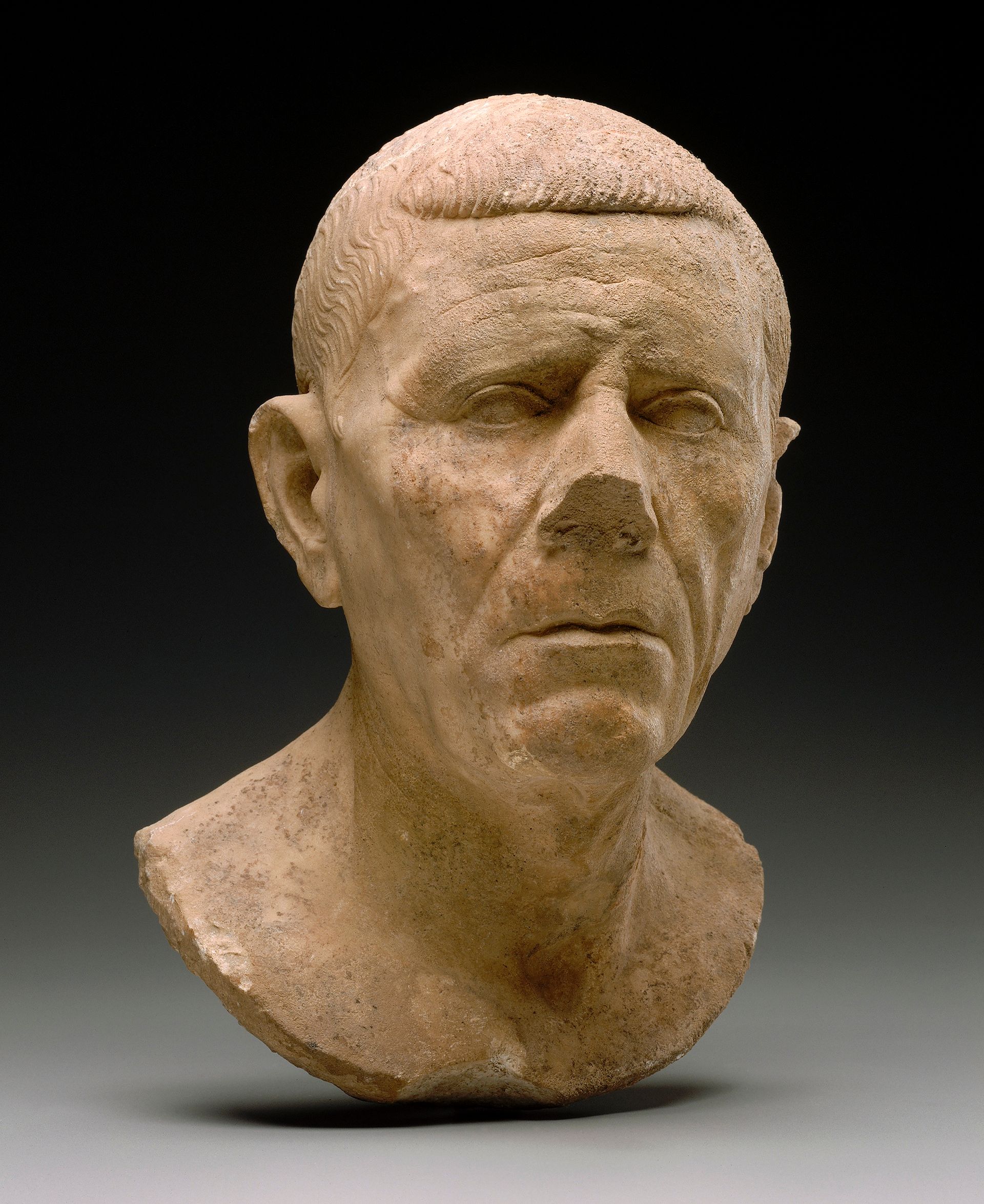

Bust of an older man, around 30 BC-AD 50, marble, from Carrara in northwest Italy. Bequest of Benjamin Rowland, Jr., by exchange, and Frank B. Bemis Fund, John H. and Ernestine A. Payne Fund, and Mary S. and Edward J. Holmes Fund Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

My interest in the myriad ways that ideas about democracy are embedded in works of art is rooted in my academic training as a specialist in Greek and Roman art. But it is also fuelled by my persistent—and possibly naive—sense of wonderment at the fact that 2,500 years ago the ancient Athenians were able to set aside their rivalries and create a new system of self-government, however imperfect and exclusive—Athenian citizens had to be free-born males of Athenian parentage.

Power of the People is first and foremost a platform for artists’ visual arguments for and in relation to democracy. It is also a demonstration of the importance of museums as places of civic learning in the 21st century. The goal of creating an educated citizenry was central to the original mission of the MFA and other American encyclopaedic museums founded in the 19th century in the image of their European Enlightenment forebears. And the MFA is a true visual encyclopaedia of democracy—and other forms of government—due to both the breadth and depth of our collections and the significant roles Boston played in the American Revolution and Abolitionism.

Museums as civic spaces

Paul Revere, Jr, Sons of Liberty Bowl, 1768. Museum purchase with funds donated by contribution and Bartlett Collection—Museum purchase with funds from the Francis Bartlett Donation of 1912 Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In the past two decades, museum educators have emphasised object-oriented learning as a path to developing a range of skills, including building civic awareness, and today there is a greater appreciation for those of us who are visual learners. When it comes to learning about democracy, art has the potential not only to build knowledge, but also elicit emotions—because each person’s lived experience of democracy is different. Art reminds us of our most celebrated citizen heroes and introduces us to the unrecognised or forgotten. It presents vaunted narratives of how democracies came to be and at the same time calls on us to question them. It demands that we confront essential questions: am I doing enough, and can I do better?

In the lead-up to the US presidential election on 5 November—the timing of our exhibition is not accidental—we are activating the MFA as a civic space. We have hosted voter registration events at community celebrations and served as an early voting location. After the exhibition opened, invited speakers, community discussions and a performance by Emerson College students of Assemblywomen, a comedy by Aristophanes from 391BC, within the gallery will further the goal of civic learning. Such programmes, especially those that occur in and among the art, make a lasting impression on audiences by inviting them to be present in the moment.

Left: Giovanni della Robbia, Judith, around 1520. Gift of Mrs. Albert J. Beveridge in memory of Delia Spencer Field. Right: Shepard Fairey, Vote!, 2008. Collection of Damon Beale. Della Robbia: Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Fairey: © Obey Giant Art Inc. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The exhibition is being installed as I write this, and now I see it finally coming together I have a few moments to reflect on its lessons and those from whom I learned. This exhibition is the result of years-long conversations about democracy within the museum and the larger community we serve. Many people contributed to making it a reality—not least the artists whose visual storytelling and arguments have shaped how we think about democracy, and who have brought about positive social change through their work.

My heroes are six teenage citizen-curators I mentored through the museum’s education initiatives. During the 2022/23 academic year, we met weekly with my curatorial colleagues to look at their collections through this lens. The teens selected objects, shared their experiences of and aspirations for democracy, debated whether “it’s a thing” and contributed label text. Their commitment, honesty, intelligence and grace make me hopeful for the future of democracy and for the role of art and museums in it.

Stanley Forman, The Soiling of Old Glory, April 5, 1976, 1976(printed 1996). Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Fund for Photography. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Phoebe Segal is the Mary Bryce Comstock senior curator of Greek and Roman Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston