“The fragment is a really important structure for telling stories that have been heavily impacted by colonialism,” the film-maker Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich has said. “For so long, value has been placed on a story that you can tell from beginning to end. For many marginalised folks, this is impossible due to trauma or lost history.”

Her The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire (2024) is one such “fragment”, a lovely, elusive film about an intriguing, elusive figure. During the Second World War, the Caribbean-born, Paris-educated intellectual Suzanne Césaire (1915-66) co-founded the literary journal Tropiques in Vichy-governed Martinique with her then-husband Aimé Césaire, and published several essays that were influential in the development of the Négritude and Surrealist movements. But she ceased writing after 1945, perhaps due to the burdens of raising six children, and faded into comparative obscurity as Aimé ascended into the canon of postcolonial poetry and politics.

With The Ballad, Hunt-Ehrlich, who presented footage from the project in installation form at this year’s Whitney Biennial, attempts to rediscover and restore Suzanne Césaire’s legacy—up to a point. A mix of historical fiction, meta-movie and essay film, her first feature film skips lightly between layers of reality and representation from an early sequence in which the camera wanders through a humid outdoor cafe, following the bodies of the dancers and onlookers until alighting on the face of the actress Zita Hanrot, returning her silent, thoughtful gaze until someone’s offscreen voice calls “cut”.

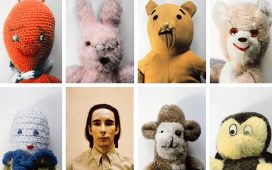

Motell Foster and Zita Hanrot in The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire (2024) Courtesy of Madame Negritude

What follows is, loosely, the story of the performer at the centre of that shot, as she studies her role. Though it’s clear from context that within the film-within-the-film Hanrot is Suzanne Césaire, Motell Foster is Aimé and Josué Gutierrez is André Breton—who stopped off in Martinique on the way to the US during his wartime exile, and was inspired by the Césaires’ revolutionary imaginations—the end credits list only the name of the actors, not of any characters. Hanrot spends much of the movie simply being, whether spending time with her newborn and the baby’s nanny (Hanrot herself became a mother shortly before the shoot), or walking between palm trees reading. In a recurring visual motif, a piece of paper—a fragment—is blown by the wind through the jungle, coming to rest who knows where, a symbol of what the director called “lost history” and her subject’s continued marginalisation.

Drawing from Terese Svoboda’s essay “Surrealist Refugees in the Tropics” and interviews with Suzanne Césaire’s children, Hunt-Ehrlich alternates between impressionistic glimpses of artistic creation and the competing obligations of motherhood on the one hand, and the firmer stuff of literature and history on the other. Snippets of essays and recollections are read aloud by the actors and in voiceover, woven through the soundtrack alongside the peaceful ambient buzz of the tropical biome (or rather subtropical: the film was largely shot in Miami). The cinematography, in 16mm, is lush and languid, and the fictional scenes are often near-wordless—moments that would, in another film, be interstitial and ephemeral.

If Surrealists like Breton found in the tropics the possibility of rejuvenation for Europe—war-torn, exhausted, at all manner of ideological and aesthetic dead-ends—then that promise, tantalising but unfulfilled, has an onscreen analogue here: Hunt-Ehrlich conjures a humming, low-key Eden more dreamt-of than returned to. And similarly, while Hunt-Ehrlich may have found in Suzanne Césaire a neglected intersectional icon who speaks to the contradictions, personal and political, of the current moment, the filmmaker equally knows that, thanks to the linearity of history, her protagonist remains incomplete, a portrait in fragments. Still, there’s freedom there—as Suzanne Césaire wrote, “Surrealism gave us back some of our possibilities.” The film’s quite funny final scene toys with our hope that this figure from the past could be an oracle in the present, and sends us out on a note of puckish open-endedness.

- The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire plays at 4pm on 6 October at the Brooklyn Academy of Music as part of the New York Film Festival